October 24, 1644–August 10, 1718

The evolving views on an early Friend’s legacy

The reputation of religious freedom advocate and early Quaker William Penn has evolved over the years since he lived in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. A close associate of the British court, Penn was an accomplished speaker and writer. He also spent time in a debtors’ prison and died in bankruptcy. Historically, he has been lauded as a proponent of tolerance and a friend to Indigenous people. He also enslaved Africans, and historians have called into question his dealings with the Lenni Lenape native inhabitants of Pennsylvania, the colony he established in 1681.

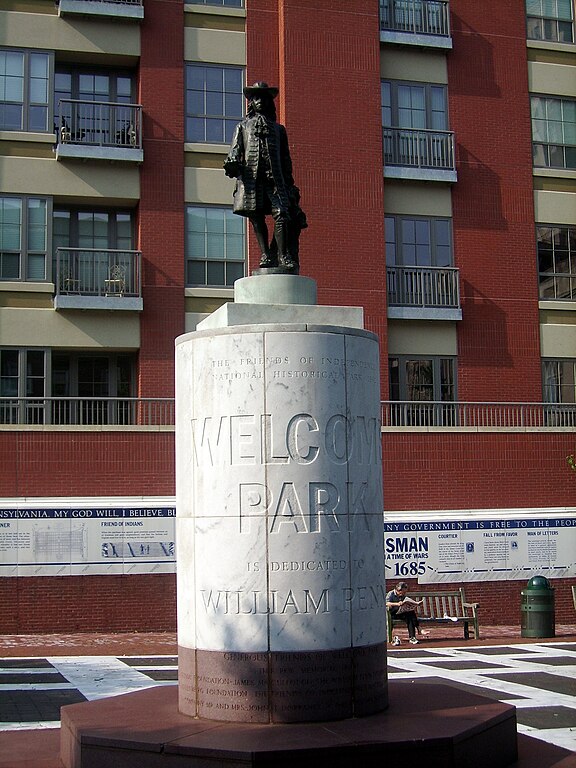

Reckoning with Penn’s morally problematic dealings with people of African descent as well as Indigenous people has led modern-day Quakers to remove his name from locations such as a room of the Friends House in London and the former William Penn House in Washington, D.C. In January 2024, the U.S. National Park Service proposed removing a statue of William Penn from Welcome Park in Philadelphia, Pa., but changed course after public comments opposing the move.

The Philadelphia Inquirer reported in 2023 that the right-wing group 24/7 National Strategic Prayer Call, which opposes LGBTQ rights and supports former president Donald Trump, embraces Penn as an example of fairness to Indigenous people. An email seeking comment from the 24/7 National Strategic Prayer Call was not answered.

Photo: Reading Tom.

Changes in how Friends view Penn reflect a broader evolution in how historians reflect on figures from the past. Historians are moving away from the “Great Men” model of history, according to Jordan Landes, curator of Friends Historical Library at Swarthmore College.

“It’s only for the good to really understand the complexities,” Landes said.

Penn was an enslaver, and there is some argument over whether he manumitted the slaves he held, according to Landes.

Penn’s 1701 will freed the people he had enslaved, but a subsequent will did not mention freeing enslaved people. It is unclear whether the silence of the second will on the matter was because Penn did not own people at the time of his death in 1718 or because he was so in debt that he did not intend to free them, explained J. William Frost, Howard M. and Charles F. Jenkins professor emeritus of Quaker history and research at Swarthmore College.

The 2009 book Fit for Freedom, Not for Friendship by Donna McDaniel and Vanessa Julye spotlighted the issue of racism in Quaker communities and discussed the limitations of Friends’ commitment to abolition of slavery. Retired Penn scholar Paul Buckley explained that the book marked a turning point in how Quakers view Penn’s moral legacy given that he enslaved people from Africa.

“Quaker historians realized that slavery is the big issue,” said Buckley, whose modern English translation of Penn’s 1696 book Primitive Christianity Revived was published in 2018.

In earlier decades, the hagiography of Penn was extremely popular. The story of Penn’s interactions with Indigenous people is nuanced, according to Buckley. Penn tried to be honest and fair in his dealings with the Lenni Lenape; he saw Native Americans as fellow children of God more so than did other people of his time, according to Buckley. Penn’s colony was taken away from him and he wrestled to get it back, Buckley noted.

“He’s a perfect example of what Jesus meant by you can’t serve two masters,” Buckley said.

Penn’s self-identification was wrapped up in proprietorship of Pennsylvania, Buckley explained. His sons, who did not share his view of Indigenous people, took over proprietorship of the colony and took advantage of the Lenni Lenape. The treaty Penn signed with the Indigenous residents of the colony was his legacy, and his sons destroyed it, according to Buckley.

Penn had intended to treat the Indigenous people fairly, and a wampum belt records one or more agreements between him and the Native Americans. However, when Penn returned to England and left his sons in charge, they did not deal honestly with the Lenni Lenape. In 1737, Penn’s sons claimed that the Lenape people’s ancestors had signed an agreement giving Penn’s family as much land as could be measured by walking for one and a half days. Instead of having people measure the land by walking on an existing path that curved near the Delaware River, Penn’s sons had a straight thoroughfare cleared. They also hired swift runners to complete the land measurement. In what became known as the Walking Purchase, Penn’s descendants fraudulently took 1.2 million acres from the Lenape.

Frost believes Penn’s writings could be read as pro-slavery or anti-slavery. Historians do not know whether Penn was aware of any anti-enslavement sentiments among Quakers of his day. In 1694, Penn was part of a special session of Britain Yearly Meeting at which Friends discussed opposition to slavery. In 1696, Philadelphia Yearly Meeting members wrote to London Quakers urging them to end the slave trade. In 1700, the minutes of the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting record Penn as advocating kind treatment of people of African descent yet establishing separate Friends meetings for them, according to Frost.

In the late 1600s, Penn enjoyed an excellent reputation, according to Frost. When James became king of England, Penn met with him in private.

“He is clearly the one Friends turned to if they needed someone to intervene with people in power,” Frost said of Penn.

After the fall of King James in 1688, Penn regained his influence; Friends widely regarded him as a great preacher. Thousands flocked to hear him in the 1690s. After 1700, he went to debtors’ prison; Friends bailed him out, but he died bankrupt. By the 1720s, Quakers started revering Penn as a hero with the public, overlooking his controversies over power, taxes, and debt. He was portrayed as a model Quaker who engages in politics. In 1726, two volumes of his writings were reprinted and used as support for Quaker belief, according to Frost. After 1800, Penn became a role model for European Americans, including the deist Thomas Jefferson who cited him as an example of religious liberty.

In the 1880s, Friends supported an international peace movement, based on Penn’s writings analyzing the causes of war and endorsing international cooperation, according to Frost. Penn’s concept of the Parliament of Europe eventually became the United Nations.

Current objections to Penn’s slaveholding gained momentum among researchers in the 1970s through the 1990s, according to Landes.

When the Friends Committee on National Legislation Education Fund acquired the former William Penn House in 2019, Quakers expressed concern about the building’s name because they objected to Penn’s having owned people, according to Lauren Brownlee, who currently serves as deputy general secretary of FCNL.

“There was enough buzz within the Quaker world that William Penn was problematic,” said Brownlee, who was serving on FCNL’s Executive Committee at that time and helped to assemble a working group within the committee to consider changing the building’s name.

Members of the working group considered naming the building after someone else. The top suggestion was Bayard Rustin, a gay, Black civil rights activist and Quaker who died in 1987. The working group sought community input and asked for public comments on the idea. Some of the commenters said they felt harmed by the fact that Rustin had expressed opposition to justice for Palestinians, according to Brownlee. Other commenters suggested that the name should reflect values FCNL wants to highlight, rather than being named after a person who would be lifted above others.

In addition to renaming the building—they settled on Friends Place on Capitol Hill—FCNL developed an antiracism statement and a land acknowledgement, according to Brownlee. As an example of FCNL’s efforts to incorporate antiracist practices into its work, Friends Place has provided housing and meals for more than 600 migrants, Brownlee noted.

The name Friends Place feels welcoming to Brownlee. To educate about the reasoning behind the name change, FCNL and Friends Place on Capitol Hill have posted online articles, held orientations, and had conversations with guests about the history of the space, noted Sarah Johnson, director of Friends Place on Capitol Hill.

Some Friends suggested keeping the name and talking publicly about the harm Penn had caused by enslaving people, Brownlee explained. One of the goals of the working group was to acknowledge that we all have good and bad aspects and that we all can sometimes cause harm. Friends of Color have felt harmed by seeing places named for enslavers, according to Brownlee.

Buckley wonders whether Penn would have wanted to have his name on rooms in Quaker buildings and similar honors. Buckley noted that Penn did not choose the name Pennsylvania: the king did. Penn’s suggested names for the colony were New Wales or Sylvania. King Charles named it Pennsylvania in honor of Penn’s late father, also named William Penn, a British admiral to whom the king owed debts.

Learn more at Friends Journal

“Neighbors or Tenants?” Francis G. Hutchins

“Rethinking William Penn,” Trudy Bayer

“Flawed Quaker Heroes,” Kathleen Bell

“Slavery in Pennsylvania,” Jack H. Schick

“A Legacy of William Penn,” Theodor Benfey

“Welcome,” Kate Bahlke Hornstein

formerly the William Penn House.

Photo courtesy FCNL.