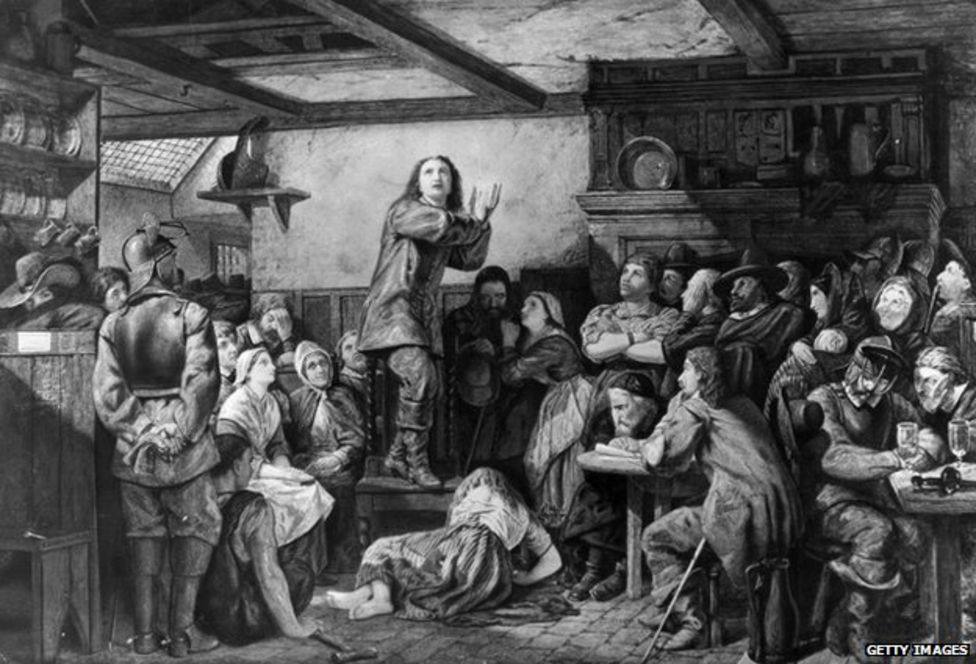

The Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) are a movement that began in seventeenth-century England. George Fox (that’s him standing on a chair to preach to a tavern crowd in the picture above) was frustrated by the Christian institutions of his day. He spent years wandering the English countryside, seeking spiritual solace, sometimes consulting with ministers and other religious leaders—but, as he later wrote, “there was none among them all that could speak to my condition.”

“And when all my hopes in them and in all men were gone,” Fox continued, “so that I had nothing outwardly to help me, nor could tell what to do, then, oh, then, I heard a voice which said, ‘There is one, even Christ Jesus, that can speak to thy condition’; and when I heard it my heart did leap for joy.” (Note: “Even” here means “namely.”)

Fox continued to roam the land, only now he began sharing the insights he gained from this and other spiritual experiences. In 1652, he met Margaret Fell, who became an active member of the growing Religious Society, and would spend several years in prison for her faith. It was there that she wrote the pamphlet “Women’s Speaking Justified,” which articulated the Quaker belief that men and women were equally capable of receiving and sharing prophetic visions from God. In 1669, having been widowed for more than a decade, she married Fox, although, between missionary work and imprisonment, they were often apart.

The early Friends sought to revive “primitive Christianity” by going back to the roots of Christianity in Jesus’ teachings around nonviolence, simple living, God’s concern for the marginalized, and the immediate and equal access to God’s Spirit. They refused to pay tithes to the Church of England, though this was a required tax at the time. They also refused to take oaths by swearing on the Bible, insisting that Jesus’s mandate to “let your communication be, Yea, yea; Nay, nay” (Matthew 5:37) was sufficient. They rejected all priestly authority and the pomp of church sacrament, choosing instead to gather in “expectant silence,” where they waited for the Spirit present among them to share whatever messages it had, choosing whoever among them it deemed fit.

(Obviously, there’s a lot to talk about between the 1650s and the 2020s—and we’ll be adding to this section over time, introducing you to other prominent figures in Quaker history.)

While Quakerism started in England and soon spread to the American colonies, today’s Religious Society of Friends is a global faith community with significant diversity in terms of its members’ theological principles and religious practices. Many Quakers still worship in silence, with no clergy presiding over the service, while other Quakers have pastors who lead their meetings in song and prayer (though silent prayer is still frequently a component of their worship). Some Friends maintain a strong connection to the Society’s Christian roots, while others choose to incorporate other religious traditions into their understanding of the divine—or even abandon belief in any divine power while remaining committed to a life of ethical conduct.

So the Quakers you meet in England might be different from the ones you meet in Philadelphia, or in Indianapolis, and those Friends might be different than the ones you meet in Nairobi or Bolivia. Set aside all the differences, though, and you’ll find that, as the anarchist Quaker scholar Ben Pink Dandelion suggests, we all share four things in common: our belief in the possibility of receiving direct communications from God, a commitment to nurturing our spiritual life through worship, a commitment to practicing spiritual discernment together as a community, and a commitment to making our lives a testimony to our faith.

Further Reading

Angell, Stephen W., and Pink Dandelion, eds. The Cambridge Companion to Quakerism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

Birkel, Michael Lawrence. Silence and Witness: The Quaker Tradition. Edited by Philip Sheldrake. Second printing edition. Maryknoll, N.Y: Orbis Books, 2004.

Dandelion, Pink. The Quakers: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press, 2008.

McDaniel, Donna, and Vanessa D. Julye. Fit for Freedom, Not for Friendship: Quakers, African Americans, and the Myth of Racial Justice. 1st edition. Philadelphia, Pa: QuakerPress of FGC, 2018.