Paul Robeson was born in Princeton, N.J. to William D. Robeson, a Presbyterian, and schoolteacher Maria Louisa Bustill Robeson, a Quaker. In 1858, his father had escaped from enslavement in North Carolina via the Underground Railroad. Maria Bustill, who came from a long family line of Friends, died in a house fire during Paul’s early childhood.

In 1915, Paul Robeson enrolled in Rutgers University, in New Brunswick, N.J., on a scholarship. He was only the third Black student to study at Rutgers, where he became both a Phi Beta Kappa scholar and an All-American football star, as well as a member of the university’s Cap and Skull Society. In 1919, as valedictorian, he used his farewell speech to address racism against African American soldiers.

After taking law classes at New York University, in the spring of 1920 Robeson transferred six miles uptown to Columbia College, attracted by the cultural vibrancy of the Harlem Renaissance. He supported himself during law school by working as an assistant coach for Fritz Pollard, head of Lincoln University’s football team (Lincoln is a historically black university located near Oxford, Pennsylvania). In 1921, he married Eslanda Cardozo Goode, a histological chemist at what is now known as New York Presbyterian Hospital.

After graduating from law school in 1923, Robeson went to work for Louis Stotesbury at an estate law firm. He excelled at legal work but encountered racism in the office. For example, a white stenographer refused to take notes for him. Robeson complained to his boss who agreed to address the issue but warned Robeson that many white clients would not hire a Black attorney. Stotesbury suggested that Robeson open a law office in Harlem and represent Black clients. Instead, Robeson resigned and changed careers.

Robeson developed a passion for acting, starring in Eugene O’Neill’s plays All God’s Chillun Got Wings in 1924 and The Emperor Jones in 1925. All God’s Chillun…concerned an inter-racial marriage, which was then illegal in the U.S. In 1925, he also played a lead role in his first film, Body and Soul, by Black writer and director Oscar Micheaux. In 1927, he played in the London show of Show Boat and became famous for his rendition of the song “Ol’ Man River.”

Paul and Eslanda Robeson’s only child, Paul Robeson, Jr. was born in 1927.

In the 1930s, Robeson moved to London where he acted in British movies and continued to perform in the U.S.S.R. and throughout Europe. In 1939, he and Eslanda returned to New York City. He supported President Franklin Roosevelt’s war effort by performing on armed forces bases, promoting military bonds, and on the Ballad for America radio broadcast. He publicly opposed fascism in Europe and racism in the U.S.

In 1943, Robeson played the protagonist in the Broadway production of Shakespeare’s Othello. The play went on a nationwide tour that deliberately omitted performances in segregated theaters.

In 1949, Robeson openly opposed war with the Soviet Union and argued that African Americans should not face conscription because the U.S. government denied them equal rights. The State Department revoked his passport the following year. Two years later, Robeson accepted the International Stalin Prize for Strengthening Peace. In reflecting on the prize, he articulated his opposition to fascism and nuclear war. A few months later, after Joseph Stalin’s death, Robeson eulogized the Soviet leader, who had ordered the execution of nearly one million of his own citizens and imprisoned countless millions more, as “wise and good—the world and especially the socialist world was fortunate indeed to have his daily guidance.”

Such views earned Robeson the lifelong hatred of American anticommunists and other right-wing conservatives, and led to an investigation by the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1956. Robeson defiantly told Congress that he would not choose to move to the Soviet Union because the labor of his African American ancestors had built the United States and that he deserved to live here just as much as his interrogators did.

In the 1958 Kent v. Dulles decision, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the State Department could not revoke citizens’ passports due to their political convictions. Robeson was free to resume performing around the world, and embarked on a concert tour of Europe, followed by a tour of Australia and New Zealand. Following Eslanda’s death from cancer in 1965, Robeson ceased public appearances due to depression and heart trouble. He died in 1976.

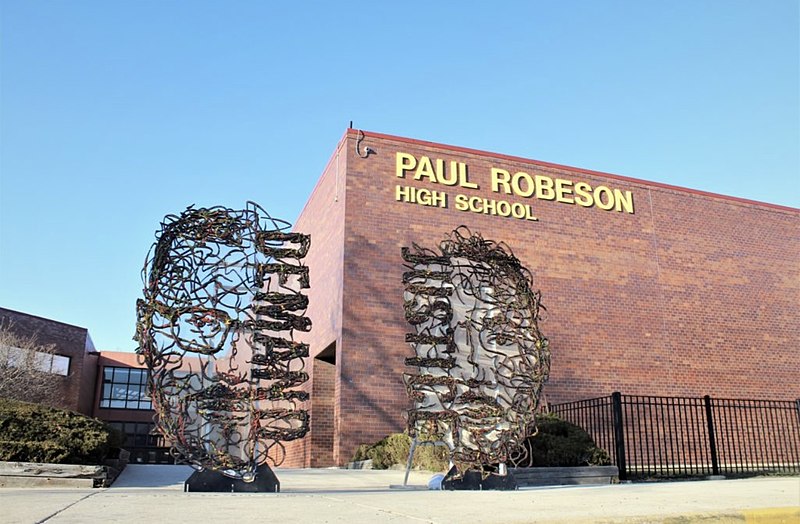

To celebrate the centennial of his graduation, Rutgers University named a campus plaza after Robeson. Columbia University offers a Paul Robeson law scholarship. Several U.S. high schools bear his name.

Suggestions for Further Reading

Here I Stand, by Paul Robeson

Paul Robeson Speaks: Writings, Speeches, Interviews, 1918–1974, edited by Philip S. Foner

Paul Robeson, by Martin Duberman

The Undiscovered Paul Robeson: An Artist’s Journey, 1898–1939, by Paul Robeson

“In Memory of Paul Robeson,” Timonthy Vaughn

Photos: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division; TukTucker (CC by SA 4.0)