Critically acclaimed author, poet, and playwright Jean Toomer (1894–1967) embraced Quakerism later in life, after he and his second wife, photographer Marjorie Content, moved from New York City, N.Y. to Doylestown, Pa. Toomer joined Buckingham Meeting in Lahaska, Pa., in 1940. He devoted much time and energy to the Quaker community in the 1940s and 1950s, advising college students, lecturing, and writing.

Toomer was best known as the author of Cane (see the 1969 Friends Journal review or read it online on Project Gutenberg), an experimental novel about Black characters migrating from the agricultural Jim Crow U.S. South to the industrialized North. He also penned the long lyrical poem Blue Meridian, which explored transcending existing concepts of racial identity.

Toomer served as clerk of the Ministry and Counsel Committee of Bucks Quarterly Meeting from 1943 to 1948. He also served on the Ministry and Counsel Committee of Philadelphia Yearly Meeting (Hickstie) from 1943 to 1945 and again from 1947 to 1951. In addition, he volunteered on Philadelphia Yearly Meeting’s Religious Life Committee from 1945 to 1947. He also ran workshops for Quaker youth at Friends General Conference Gatherings and wrote the booklet An Interpretation of Friends Worship for Friends General Conference.

In 1949, Toomer delivered the William Penn Lecture at the Arch Street Meeting House in Philadelphia. He referred to George Fox and other early Quakers as people who radiated Christ’s Light even as they were beaten and incarcerated. He described an internal spiritual lack leading to frustration as the source of racial conflict, class strife, and war. Fighting leads to more spiritual poverty and frustration, which, in turn, leads to more combat, according to Toomer.

He offered a Christ-centered solution, saying, “Christ came to open the way between men and the Eternal Being, that we might have life and have it abundantly.”

In 1922, Toomer took a job as a substitute school principal in Sparta, Ga., at the Sparta Agricultural and Industrial Institute near communities in which his father had lived. Toomer’s brief time in Georgia inspired him to write about the lives of African American Southerners during the Jim Crow era. The result was Cane, his well-received 1923 book combining poetry and prose. In 1936, he published Blue Meridian, a long poem about developing an “American” race that combines people of various heritages, including African American, European, and Native American.

Toomer’s parents, Nathan Toomer Sr. and Nina Pinchback Toomer, divorced in 1898, a few years after he was born. Toomer’s given name was Nathan Pinchback Toomer; he took the pen names Jean Toomer and N. Jean Toomer. Nathan Toomer Sr. was a formerly enslaved person. Jean Toomer was raised by his mother and grandfather, a former Union soldier who had served as the acting governor of Louisiana during Reconstruction—the first African American to hold such a post. Jean Toomer’s paternal great grandfather was a White planter and his paternal great-grandmother was a biracial enslaved person.

Toomer grew up in an affluent White section of Washington, D.C., and attended the all-African American Paul Laurence Dunbar High School. He later moved with his mother to predominantly White suburbs in New York State where he attended a mostly-White school.. Toomer rejected traditional racial classification and moved in social circles with Black and White people.

Before becoming a Quaker, Toomer spent decades following the teachings of mystical philosopher George Ivanovich Gurdjieff. He visited Gurdjieff’s Institute for the Harmonious Development of Man in Fountainbleau, France, in 1927 and 1929. At the Institute, followers performed rigorous physical labor as a way of purifying themselves and integrating their inner lives. After returning to the United States,Toomer established study groups to instruct others in Gurdjieff’s teachings, which dovetailed religion with psychology.

Toomer died in 1967 in Doylestown. He was predeceased by his first wife, writer Margery Latimer, who died in 1932 giving birth to their only child, daughter Margery. He was survived at the time of his death by his second wife, Marjorie Content, a stepson, Jim Loeb, and a stepdaughter, Susan Loeb.

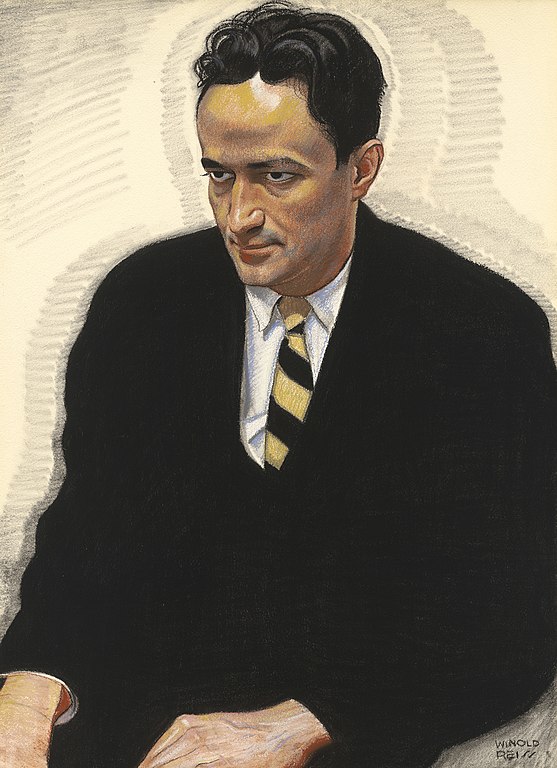

Illustration: 1925 drawing of Jean Toomer by Winold Reiss, at the National Portrait Gallery.