March 17, 1912–August 24, 1987

Raised by his grandparents, Julia Davis and Janifer Rustin, Bayard Rustin learned Friends’ values and practices from his grandmother as he grew up in West Chester, Pennsylvania.

Drawing on his Quaker commitment to equality and the organizing he learned at his grandfather’s African Methodist Episcopal church, Rustin devoted his career to non-violent direct action against racism. He maintained a lifelong commitment to pacifism which influenced Martin Luther King, Jr. , who relied on him as an advisor.

During World War II, Rustin spent two years in prison as a conscientious objector. Although Rustin’s Quaker faith could have kept him out of prison, he chose to go to jail to protest discrimination against non-religious conscription resisters. He served a two year sentence at Ashland Federal Correctional Institution in Kentucky where he wrote a letter to the warden objecting to racial segregation at the prison. The warden integrated the weekly Sunday recreation time when inmates listened to the radio broadcast of the New York Philharmonic. A white prisoner physically attacked Rustin for his integration work, which eventually resulted in less segregation in the prison.

Starting in 1947, Rustin worked as treasurer of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and the co-secretary of race relations for the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR). From 1954 to 1965, he served as the executive secretary of the War Resisters League. In addition, he helped found the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

In 1947, he participated in the Journey of Reconciliation, a two-week trip in which eight Black men and eight White men tested the implementation of the 1946 U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Morgan v. Virginia, which declared segregation on interstate buses unconstitutional under the commerce clause. Police arrested group members on six of their 26 bus rides. Rustin served an approximately three-week sentence in a chain gang. His journalistic reporting on the experience led to improved treatment of prisoners in chain gangs.

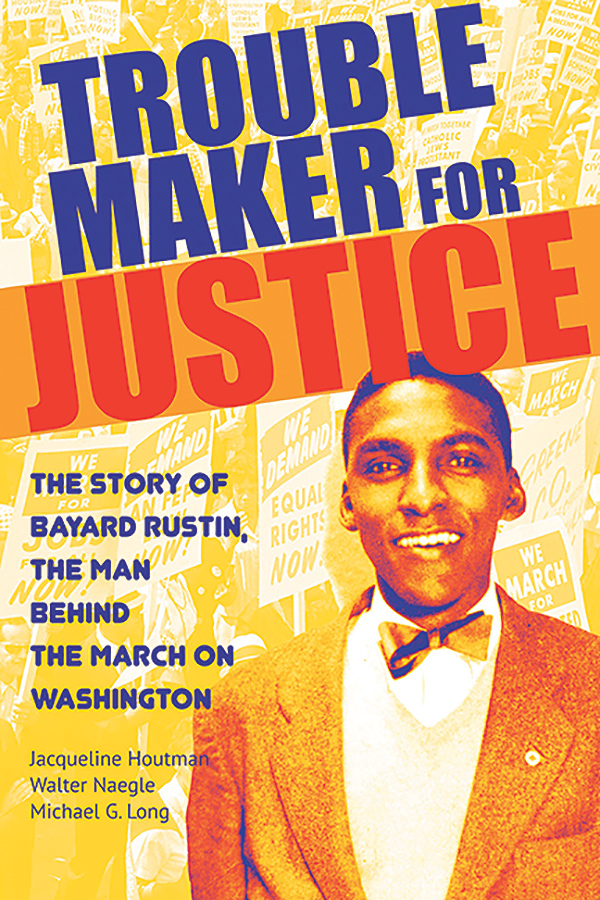

Rustin planned the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom at which King gave his “I Have a Dream” speech. However, his role as an organizer was downplayed due to concerns among others in the civil rights movement about his youthful Communist connections and his gay identity, the latter of which already having cost him his position at FOR. (In 1953, police in California arrested Rustin for sexual activity with two other men; he spent 50 days in jail and was registered as a sex offender. It took until 2020 before he was posthumously pardoned by the state’s governor.) In later years, as public attitudes towards homosexuality changed, Rustin grew more outspoken in his gay rights activism and also became a vocal advocate for people living with AIDS.

And, too, the world at large began to become more aware of Rustin and his contributions. Today, many public places—including schools, community centers, parks, and streets—bear his name, and his final residence, in an apartment building in New York City’s West Chelsea neighborhood, is on the National Register of Historic Places. In 2013, roughly a quarter-century after his death, President Barack Obama posthumously awarded Rustin the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Learn more at Friends Journal

“Human Rights: The Central Issue of Our Time,” Bayard Rustin

“Bayard Rustin: Out from the Shadows of History,” Brian Ward

“The Duty to Resist,” Carlos Figueroa

“Bayard Rustin at Swarthmore College,” Newton Garver

Sources Cited

The Martin Luther King, Jr. Encyclopedia, Stanford University

“The ‘Roving Ambassador:’ Bayard Rustin’s Quaker Cosmopolitanism and the Civil Rights Movement,” Sebastian C. Galbo