Long ago God spoke to our ancestors in many and various ways by the prophets, but in these last days he has spoken to us by a Son, whom he appointed heir of all things, through whom he also created the worlds. He is the reflection of God’s glory and the exact imprint of God’s very being, and he sustains all things by his powerful word.

(Hebrews 1:1-3, New Revised Standard Version, Updated Edition)

I have heard of your faith in the Lord Jesus and your love toward all the saints, and for this reason I do not cease to give thanks for you as I remember you in my prayers, that the God of our Lord Jesus Christ, the Father of glory, may give you a spirit of wisdom and revelation as you come to know him, so that, with the eyes of your heart enlightened, you may perceive what is the hope to which he has called you, what are the riches of his glorious inheritance among the saints, and what is the immeasurable greatness of his power for us who believe, according to the working of his great power.

(Ephesians 1:15-19, NRSVUE)

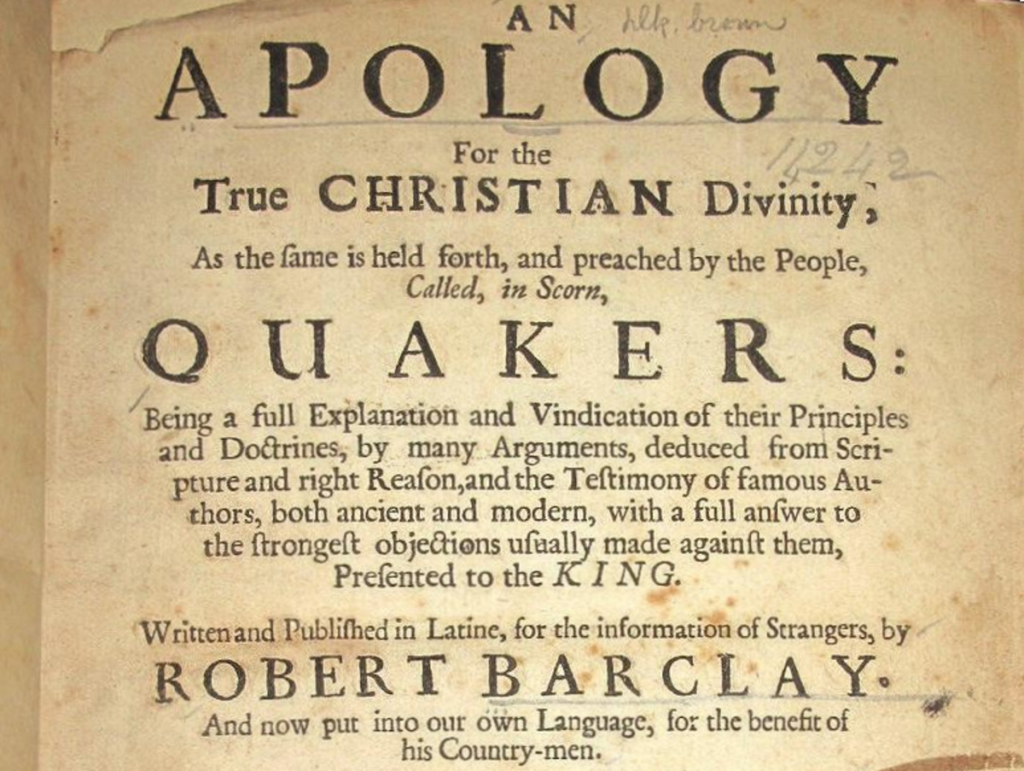

In the late seventeenth century, Robert Barclay emerged as a compelling systematic Quaker theologian.

His Apology for the True Christian Divinity vigorously defended Quaker faith against the English religious establishment’s accusations of blasphemy in a series of firm, confidently asserted propositions.

Barclay’s second proposition, for example, declared that “the testimony of the Spirit is that alone by which the true knowledge of God hath been, is, and can be only revealed.” As such, in the past, “[God] hath manifested himself all along unto the sons of men, both patriarchs, prophets, and apostles,” and “[these] revelations of God by the Spirit, whether by outward voices and appearances, dreams, or inward objective manifestations in the heart, were of old the formal object of their faith, and remain yet so to be, since the object of the saints’ faith is the same in all ages.”

Yet while the Scriptures contain records of God’s previous revelations, Barclay describes them later in the Apology as “only a declaration of the fountain, and not the fountain itself… [and] not to be esteemed the principal ground of all Truth and knowledge.” The Bible might tell you what God had revealed to others, but you had to ask yourself: What message does God have for me?

If you couldn’t answer that question, you needed to listen more keenly.

This gets at one of the fundamental points of contention between the early Quakers and the religious establishment of their time. Friends viewed direct contact from Spirit, and the communion that followed from it, as central to their religious identity. Without the sustenance of that powerful word, you weren’t following the exact imprint of God’s very being, no matter how sincere your efforts. Instead, you might well wind up following some man passing off his own agenda—or the agenda of an ecclesiastic institution—as Christ’s. (Men dominated the religious establishments of seventeenth-century England; that Quakers accepted women as recipients of divine revelation made them further outcasts.)

“Of old none were ever judged Christians, but such as ‘had the Spirit of Christ,’” Barclay observed, quoting Romans 8:9. “But now,” he lamented, “many do boldly call themselves Christians, who make no difficulty of confessing they are without it, and laugh at such as say they have it.” In our time, too, we can find many who boldly call themselves Christians, but do not follow where Spirit leads—choosing, instead, to live according to the flesh (Romans 8:12-14) while mocking others for embracing such principles as charity and empathy toward their neighbors.

(Some Friends today find all this Christ talk limiting. If you count yourself among them, feel free to substitute whatever ecumenical or universalist language makes you more comfortable.)

Of course, all sorts of religious institutions can fall prey to the temptations of the material world, not just Christian churches. Even Quaker meetings can succumb to greed and covetousness if they lose sight of the reflection of God’s glory. We all need to keep the eyes of our heart firmly fixed on the Inward Light.

For the spirit of wisdom and revelation works among us still.

Fox and the other early Quakers knew in their hearts that God was calling them to hope at that very moment. They knew that if enough people embraced the promise behind that summons, the corrupt principalities of their world would fall, making way for the beloved community they were meant to inherit, where peace and justice would never falter.

And what of Friends today? What do we believe guides us along the moral arc of the universe? Our own notions of right and wrong, or a call to hope from beyond the limits of human consciousness? Do we work to preserve secular society as it stands and carve out our fortunes within it? Or do we listen for the testimony of the Spirit, and its invitation into a more perfect world?

Comments on Friendsjournal.org may be used in the Forum of the print magazine and may be edited for length and clarity.