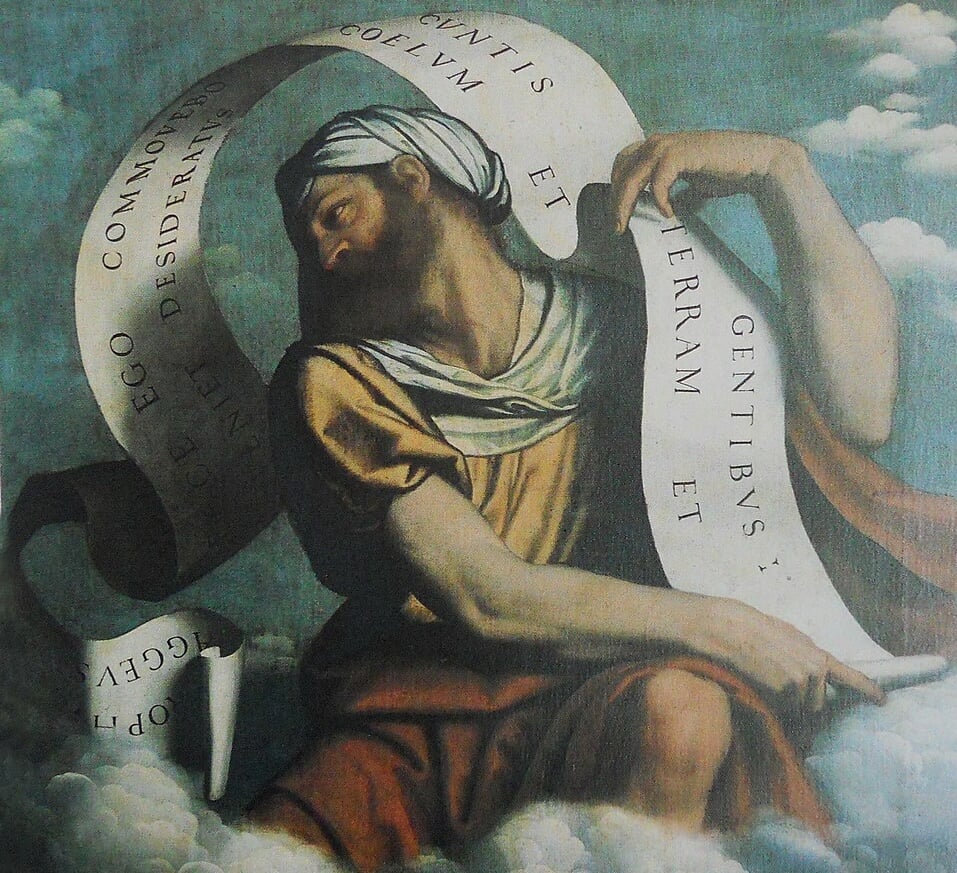

In the seventh month, on the twenty-first day of the month, the word of the Lord came by the prophet Haggai, saying: “Speak now to Zerubbabel son of Shealtiel, governor of Judah, and to Joshua son of Jehozadak, the high priest, and to the remnant of the people, and say: Who is left among you who saw this house in its former glory? How does it look to you now? Is it not in your sight as nothing? Yet now take courage, O Zerubbabel, says the Lord; take courage, O Joshua, son of Jehozadak, the high priest; take courage, all you people of the land, says the Lord; work, for I am with you, says the Lord of hosts, according to the promise that I made you when you came out of Egypt. My spirit abides among you; do not fear. For thus says the Lord of hosts: Once again, in a little while, I will shake the heavens and the earth and the sea and the dry land, and I will shake all the nations, so that the treasure of all nations will come, and I will fill this house with splendor, says the Lord of hosts. The silver is mine, and the gold is mine, says the Lord of hosts. The latter splendor of this house shall be greater than the former, says the Lord of hosts, and in this place I will give prosperity, says the Lord of hosts.”

(Haggai 2:1-9, New Revised Standard Version, Updated Edition)

I take part in unprogrammed Quaker worship, where we don’t read from the Bible at meetings—not on the schedule various Christian churches do, at any rate. So I wonder, sometimes, how the readings on which I base these messages might land on a Sunday morning.

What would you make of this passage from the Book of Haggai?

Haggai lived, six centuries before the birth of Jesus, in a Jerusalem devastated by the invading forces of Babylon’s King Nebuchadnezzar, its high temple burned to the ground. Two generations would pass before the Persians conquered Babylon and allowed descendants of the Judeans Nebuchadnezzar had exiled from the city to return.

This sets the stage for Haggai’s prophetic announcements to Judah’s governor and high priest—and, by extension, the entire Judean community. He begins by acknowledging the public sentiment against restoring the ruined temple: “These people say the time has not yet come to rebuild the LORD’s house.” (1:2) Instead, they are looking out for their own fortunes. How was that working out for them, Haggai wonders? “Consider how you have fared…”

“You have sown much and harvested little; you eat, but you never have enough; you drink, but you never have your fill; you clothe yourselves, but no one is warm; and you that earn wages earn wages to put them into a bag with holes.” (1:5-6)

“My house lies in ruins, while all of you hurry off to your own houses;” until that changes, the LORD reiterates, these conditions will continue. (1:9) Haggai’s speech has the intended effect, “stirring up the spirits” of the Judeans and spurring them to get to work on the temple. Three weeks into the project, Haggai comes back to the governor and the high priest, asking rhetorically: “Who is left among you who saw this house in its former glory?” A brutal question for a people born in exile, only recently returned to their ancestral homeland.

And, at least as I read it, a brutal question for Americans in 2025.

I’ve lived in the United States for more than half a century, and I’ve never seen our constitutional republic in as precarious a position as we find it today. I’ve never seen as many people on the brink of material calamity as I do today. I grew up hearing stories of such a time, in my grandparents’ youth, when all the world succumbed to economic depression and much of the world fell to authoritarianism. Stories grim enough to make me wish, as Frodo Baggins says in The Fellowship of the Ring, “that it need not have happened in my time.” Well, to paraphrase Gandalf’s reply, nobody wishes for such times—but what will we do now that they’ve arrived?

Last week, I attended the Freedom Rising conference at the Middle Church in lower Manhattan, where I heard the United Church of Christ pastor Otis Moss III speak about prophetic grief. When prophets express grief, they acknowledge the severity of their society’s present circumstances. “How does it look to you now?” as Haggai asked the Judeans. “Is it not in your sight as nothing?” Yet they refuse to abandon hope, or accept defeat. “Take courage,” God says, “for I am with you… according to the promise that I made… do not fear.”

“I recognize what is happening,” Moss said of such moments. “I feel the pain, but I will not fall into despair.” He spoke of the women who worked behind the scenes during the Montgomery bus boycott, how they spurred their community to take action and how they kept the momentum going. And he reassured us that “there’s some spiritual guerrilla warriors in America at this moment,” too.

“We may not be winning,” Moss conceded, “but we’re not losing.”

What might winning mean for us? The translation of Haggai above, I think, obscures the matter somewhat when God promises to “fill this house with splendor” and “give prosperity,” echoing the references to treasures and gold and silver. Other translations render the Hebrew words kabowd as “glory” and shalom as “peace,” choices which seem to me especially apt.

Though each term can carry connotations of abundance and wealth, I believe God offered the ancient Judeans—and offers us now—more than material success. When we choose to “buy into” the covenantal relationship, by loving God and loving our neighbors as ourselves, we work toward creating a community grounded in the stability of peace, a true glory to behold. And we can live to behold it—if we keep putting in the work.

Comments on Friendsjournal.org may be used in the Forum of the print magazine and may be edited for length and clarity.