The One Who Got AwayNote: Following in the spirit of Jack Powelson's fine autobiographical letters, I offer this one about my first real experience with suffering and charity. I wrote this several years ago, and it remains one of my favorite essays. — Loren

Once, a long time ago on a Saturday morning, I took my bike and explored outside my neighborhood. We lived at that time in Lahore, Pakistan, in the upscale Gulbarg area, around the corner from a refugee camp. I was 12, or maybe 13, and filled with boyish energy and innocence. Our house, a stately affair with formal garden in front and walled servant's compound at the rear, was one of a dozen or so along a beautiful tree-lined dirt road that ran up to the main canal. At the beginning of the road lay the refugee camp, with tiny single-family hovels scattered around the edge of a common area where boys played cricket and water buffalo grazed peacefully. An enormous shade tree dominated the entrance, dividing our street from the camp. At the foot of the shade tree was an open-air bicycle repair shop, a perpetual beehive of activity and gossiping neighbors. My normal route to school took me down our road and to the left around the repair shop, and then onto the paved road which wound through Gulbarg proper. But today I went to the right. In Pakistan, as in all Muslim countries, beggars are almost everywhere. This is quite a shock to newly arrived Americans; in fact it is usually harder to adjust to the beggars than to any other feature of life in Pakistan — harder than the poverty, harder than the smells, harder even than the heat and flies and lizards and exotic foods. But giving to beggars is sacred in Islam, and realizing this fact is essential for every foreigner. When an American is seen refusing a beggar, and shooing him away, it is understood to be a sign of spiritual emptiness within the American, not as humiliation for the beggar. This lesson I had not yet internalized, and I was still at that awkward stage of embarrassment whenever confronted with an outstretched hand. Around the tree and to the right I cycled, waving to the boys my age who were fixing flats in the cool shade. I ventured down a side street, and came to a small intersection. Looking down the crossroad, I felt as though I had suddenly shifted a hundred years into the past. Not a single car or motorcycle was to be seen, only peasants carrying huge loads on their heads, and a very few riding on bicycles. The houses that lined the street were small and dirty, and everyone seemed to be dressed in rags. I stopped and stared, amazed at finding such a scene within the booming city of Lahore. Looking back now, I realize I had stumbled into the tiny old village of Gulbarg, hidden away in a small corner within the modern subdivision that had grown up around it and become a suburb of the Lahore metropolis.

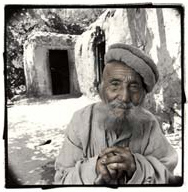

An old man emerged, bright white eyebrows and white beard accenting his nut-brown wrinkled face. He carried a heavy load of wood on his back, and his sandals were in tatters. He walked right up to me, the rich American kid, held out an ancient hand and muttered a formulaic plea in Punjabi. Unlike my experience with so many other beggars, I sensed immediately a deep and critical need, possibly days-old hunger. I looked in his eyes while he stood straight and looked in mine. Something connected between us, but I was confused by the unfamiliar sensation. I shrugged and shook my head, an automatic response, while deep inside I wondered what was going on. He turned away, and as he turned he said, "Na, na, na," a remark that I understood as clearly as if he had said in English, "Of course not, you're only an American, what do you know of hunger." I stood transfixed for a moment, seeing nothing at all, then realized that the old man had gone. There was nothing to do but return home. His face and his words have haunted me ever since. He was truly a man in need, and I had sensed that need as clearly as if it had been my own, but I missed the moment and let it slip away. That night I vowed never to let that happen again. Over the years since then, I've slowly learned a few things about human pain and suffering. I've stood looking down at the dead body of my best friend, violently killed by an arsonist's torch. I've spent long hours in the middle of the night, helping kids who were tripping their brains out on LSD reconnect with reality and find their place in the world again. I have friends in prisons and mental institutions, and friends who live their lives in mental prisons, suffering invisible tortures of utter panic and despair, knowing more psychic pain in a single night than most people experience in a lifetime. I know several courageous souls who live with divided selves in a single body, for whom "memory" and "self" are concepts more elusive than most people can ever imagine. And through it all, with every person I have ever met, I find a connection that harks back to my boyhood experience with the one who got away, that old beggar in Pakistan. Sometimes it's a curious gesture, sometimes a hidden glance or a peculiar turn of phrase, but always there comes a moment when, face to face with a new acquaintance, an entire world of emotional presence and selfhood opens up, and I see as clearly as if in broad daylight the shape and substance of a human soul. I see the brave adult front that is presented to the world, I see a child playing, and I see a confused teenager and a baby crying. A part of me reaches out and recognizes each and every one, and a two-way flow begins that nourishes my soul and starts a new friendship.

"How can life have meaning, when it is so filled with suffering?" This is an ancient question, which I have had to face many times. Some phrase it in an older way, asking "How can there be a God, when life is so filled with suffering?" No verbal or symbolic answer, no written words, no mathematical formula can ever prove adequate to this question. But I do know how the meaning of life can be lost: if I should lose awareness of that two-way underground river that flows between us, then the meaning of our shared life together (and, in the elder idiom, the grace of God) will have departed from my path. Thus I believe that, for life to have meaning, at least two things are necessary: the bond between mother and child, which forms our earliest and warmest experience of connection, and the experience of "the one who got away," when first we meet the suffering of another human being. This second experience is crucial, because it quickens the great rivers that flow between lonely humans, bringing meaning and joy to life. Sincerely your friend, Loren Cobb Readers Comments:Note: Please send comments on any TQE, at any time. Selected comments will be appended to the appropriate letter as they are received. Please indicate in the subject line the number of the Letter to which you refer! The email address is tqe-comment followed by @quaker.org. All published letters will be edited for spelling, grammar, clarity, and brevity. Please mention your home meeting, church, synagogue (or ...), and where you live.Great story, well told — the flip side of my experience in India when my Indian friends urged me never to give to the beggar children because many of them had been kidnapped by beggar gangs (and even maimed) for this purpose, and giving to them would help perpetuate the system. Is there an economic piece to your story? Are the economic implications? Rich kid, poor man, yes. But, are you saying that people should always share what they have with whomever appears to have need? Or to have less? Are you suggesting this is a moral imperative, regardless of the economic impact, micro or macro? Is this part of a larger mandate, or a larger system, or just sort of a stand-alone example of our common humanity regardless of the economic implications? — Norval Reece, Newtown (PA) Meeting. We were told the same thing in Pakistan, and I saw many children who were part of such begging rings, often with both legs broken so as to appear even more needy. One adult beggar whom I knew and liked had been maimed in this way as a child, but through sheer force of personality had emancipated himself from his master. He always dressed in a clean blue business shirt, and pulled himself around on a little cart, much like Porgy in Gershwin's opera. Thanks for asking about the economic and moral implications of my story, it gives me a chance to explain myself. I wanted to bring out the spiritual and emotional bedrock that underlies empathy for the suffering of others. This lies well below the surface economic aspects of charity and financial aid, whether personal or institutional. It also underlies — and makes possible — all morality and ethics. I believe that without a solid spiritual and emotional foundation, morality and charity are just empty social formalisms, devoid of meaning. — Loren Loren, what a kind and touching letter. It brought tears to my eyes. Thank you very much. — John Spears, Princeton (NJ) Friends Meeting. My question is different: How can you not know God through the wonders, intensity, joy, beauty and simplicity that is our universe? Thank you for sharing this experience. — Christopher Viavant, Salt Lake City (UT) Meeting. Let us not forget that atheists also appreciate the wonders, intensity, joy, beauty, and simplicity of our universe. What does it mean, "to know God?" In this essay I was groping toward an unconventional interpretation of the phrase, grounded in the experience of spiritual connection rather than any external or internal entity. — Loren My wife, Bernadette, and I are both physicians in our late 50's who are beginning two years of service in a remote Mayan village in the mountains of Guatemala. Your story touched me and made my heart ache. There is so much we Americans take for granted and so much we can and should do. Thanks for putting some of those insights into such beautiful words. — Jack Page, Atitlan, Guatemala. I enjoyed your essay. An old friend once said to me: "Read Gandhi, and maybe Schweitzer; you don't need to look much further for wisdom." They understood economics as well! Mewn gyfeillgarwch (in friendship) — Dai Jenkins, Quaker from Aberystwyth, Wales, U.K. Hmmmm. I may have to write a future TQE on Gandhi's economics. It might surprise you! — Loren ABOUT TQERSVP: Write to "tqe-comment," followed by "@quaker.org" to comment on this or any TQE Letter. (I say "followed by" to interrupt the address, so it will not be picked up by spam senders.) Use as Subject the number of the Letter to which you refer. Permission to publish your comment is presumed unless you say otherwise. Please keep it short, preferably under 100 words. All published letters will be edited for spelling, grammar, clarity, and brevity. Please mention your home meeting, church, synagogue (or ...), and where you live. To subscribe, at no cost, visit our home page. Each letter of The Quaker Economist is copyright by its author. However, you have permission to forward it to your friends (Quaker or no) as you wish and invite them to subscribe at no cost. Please mention The Quaker Economist as you do so, and tell your recipient how to find us on the web. The Quaker Economist is not designed to persuade anyone of anything (although viewpoints are expressed). Its purpose is to stimulate discussions, both electronically and within Meetings. PUBLISHER AND EDITORIAL BOARDPublisher: Russ Nelson, St. Lawrence Valley (NY) Friends Meeting Editorial Board

Members of the Editorial Board receive Letters several days in advance for their criticisms, but they do not necessarily endorse the contents of any of them. Copyright © 2005 by Loren Cobb. All rights reserved. Permission is hereby granted for non-commercial reproduction. |

Dear Friends,

Dear Friends,

Some people say they find the voice of God in holy scripture, or embodied in the voice of religious authority, or in that "still, small voice from deep within," accessible only by silent meditation and prayer. For me it is different. My spiritual moments come in those moments of discovery, when I connect with another human being. God speaks to me then not with a whisper but the roar of a mountain stream, sweeping us irresistibly along to an unknown shared experience, just around the bend.

Some people say they find the voice of God in holy scripture, or embodied in the voice of religious authority, or in that "still, small voice from deep within," accessible only by silent meditation and prayer. For me it is different. My spiritual moments come in those moments of discovery, when I connect with another human being. God speaks to me then not with a whisper but the roar of a mountain stream, sweeping us irresistibly along to an unknown shared experience, just around the bend.