Loving the Universe

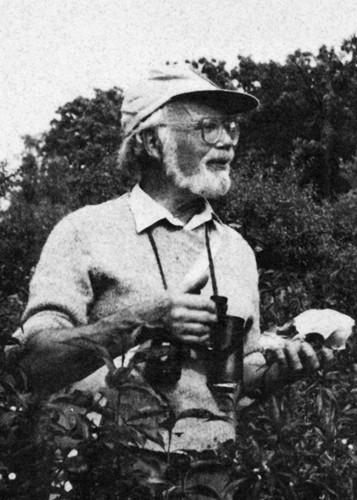

Bill Howenstine

The 1992 Jonathan Plummer Lecture

Presented at

Illinois Yearly Meeting

of the

Religious Society of Friends

McNabb, Illinois

July 26, 1992

Introduction of William L. Howenstine

Born and raised near the edge of a small town in Ohio, Bill Howenstine was fortunate to be part of a loving and supporting family, living only a long block away from the woods and fields that he early came to love. A childhood illness and a summer camp became powerful influences in his life, which centered increasingly on people's relationships with nature.

College included undergraduate work at the University of Arizona and graduate study at the School of Natural Resources, University of Michigan. His employment has included extensive camp work, outdoor education for the Cleveland Heights Public Schools, and, since 1961, teaching and administration at Northeastern Illinois University in Chicago.

In 1951 Bill and his wife, Alice, joined the Religious Society of Friends and were married under the care of the Cleveland Friends Meeting. In the summer of 1964 they were directors of an American Friends Service Committee community service project in the state of Tlaxcala, Mexico. A year later they went to Lima, Peru, to spend 13 months as directors of an AFSC community development program.

Parents of three grown children, at the present time Bill and Alice live on a tree farm, are members of the McHenry County Friends Meeting, and serve on the Steering Committee of the Friends Committee on Unity with Nature.

Loving the Universe

Thank you for this opportunity to share my story with you and for the mutual friendship with this event implies. Thanks, also, to those of you who gave me suggestions. You know, Quakers commonly make suggestions in the form of a question, like, "Are you going to make us laugh?" A group of you who know my tendency to procrastinate conspired, it seems, to ask repetitively throughout the year, "Have you started your lecture yet, Bill?"; "How is the Plummer going, Bill?"; "Are you about done now, Bill?" Alice, who is my wife, was more direct: "Don't tell us to stop slapping mosquitoes!"

When I was asked to give this talk it was suggested that I describe the path by which I arrived at my present beliefs. I like that figure of speech because I have walked so many real paths in so many places, some of them broad and hardpacked by the many who have gone before me, a few, like an overgrown canoe portage trail in Canada, difficult to follow even with blazes on the trees. These paths, both real and figurative, have led me here, and to the realization in myself of simple truths expressed by many others in many ways over many years: God is Love; the Love Spirit is the Creative Force which brought about and permeates this universe; as an intelligent being I have the responsibility and joy of using this love force within me -- loving the universe.

But I have found that one does not love the universe easily. I think I have been trying for as long as I can remember. It is difficult enough to really love one thing. How does one love everything?

I was lucky to have a headstart through the accident of my birth, having the good fortune to be part of a family where love was the way of life. To be sure, I was sometimes scolded by my parents in ways that did not seem loving to me at the time, and my brother and two sisters and I sometimes engaged in good, old-fashioned sibling fights. We all shared honest anger with each other. But these were merely superficial flaws, like the scratches or nicks on a valuable old antique. At the heart of things was a permeating love that bound us together then, and which still does. Our family was a teaching laboratory where love as the Creative Force was demonstrated in innumerable forms and where love as the means for building community could be practiced over and over without serious risk.

By the time I reached high school I was already aware of my good fortune and hurt by the apparent injustice suffered by others in the nature of their birth. Later, I came to realize that fortune, good or bad, is very much a matter of one's perspective. Each of us has a mix of good fortune and bad fortune, has a mix of strengths and weaknesses. As members of the universal community we have a responsibility to use our fortunes, our strengths, our talents as creatively as possible for the benefit of that community. That, simply put, is loving the universe.

After my family, the next most important thing to me as a child was my woods. I didn't own it in the legal sense, but in the sense of a loving belonging it was mine, and I was its. Only one block from my home on the edge of a small town in Ohio, it was my refuge, my recreation, my friend, my teacher.

I remember so clearly the emotions I felt as a young boy standing alone on a late winter day among the pin oak trees, sad at the disrespectful hacking of an oak by some of my friends, whom I let wander off without me. From my mouth came The Omaha Tribal Prayer: "Wakonda, dhe, dhu, wapathin, atonhe" ("Great Spirit, a needy one stands before you; I that sing am he.") It was a song I had seen in The Book of Woodcraft by Ernest Thompson Seton, the tune of which I picked out on the family piano. I did not know how to pronounce the words, and still don't, but it spoke to my condition and to my friendship with the injured tree.

But my friends had their own appreciation of the woods. One year we organized the "Forest Patrol", riding our bikes over the trails on the lookout for danger to our woods. We were radical extremists -- Earth Firsters before Earth First was organized. For example, one day we tore down some coffee can sap buckets and their spouts, which older kids had put on the trees for maple sap. We didn't want anyone drilling holes in our trees! (Ironically, now we tap our own maple trees in the front yard each spring to make maple syrup! See how difficult loving the universe is!)

Another day we found some "FOR SALE" signs posted on trees on a vacant lot at the edge of the woods, and tore them down, hoping that would slow the inevitable development.

Our most loving act, perhaps, was the reforestation project. In the late 1920's a subdivision had been planned for our woods, and streets had been cut through it. The Great Depression stopped the development before the streets could be paved, and plant succession had begun, with the invasion of goldenrod, Queen Anne's lace, and wild asters. Hoping to hasten the succession and grow trees that might help thwart the developers, we dug up a small wagon load of bur oak seedlings and transplanted them up and down the street beds.

How we loved that woodland and the fields beyond it! So many other experiences could be related -- the overnight camping, the cold, winter Sunday afternoon hikes followed by hot chocolate at home, the ponds with chorus frogs and water insects, the ephemeral spring flowers, the blackberry picking, the terrifying flight across the far pasture to escape curious horses on a foggy morning ...

Through it all we children learned to love nature. We didn't know the term "ecosystem", but bit by bit we loved more and more, sensing, almost unconsciously, how one part was connected to the others. And I learned how important it is that each of us have some spot of nature to nurture us early on. For most kids the day has passed when this can be provided by one's own farm -- or by some adjacent, undeveloped property. My childhood woods is now destroyed by houses, and the possibilities of hunting butterflies, picnicking, or hiking on most any country land along most any country road do not exist today. Modern farming seldom leaves a wild fencerow or a horse pasture. Strong fences, "NO TRESPASSING" signs, and the general suspicions and fears born of our present violence-prone society argue against such informal sharing of private land.

There were other learnings from my woods. One, strangely, was the benefit of reading. Ernest Thompson Seton's Book of Woodcraft, his children's novel, Two Little Savages, and his wildlife stories, like "Silverspot, the Crow", became my environmental "bible" before the "environmental movement" began to move. Experientially based as much of my learning was, I did not forget the importance of the printed page, reinforced daily by the presence of a family library. Years later, when I became a professional teacher, it bothered me to see teachers who never took their children out of the classroom, but it also bothered me to hear advocates of outdoor education exclaim that the "real-life experiences" of the outdoors are the only "real way to learn." I learned the Omaha Tribal Prayer from a book, from experiencing it on the piano, through my own singing, and by feeling it in the context of love for a tree. All of these ways of learning are needed.

So you see, something else was forming in my subconscious -- the beauty and worth of diversity -- diverse ways of learning and diverse forms of life. My brother, who was some 11 years older than I and experienced as a nature counselor in a summer camp, sometimes led the rest of us in woods walks, sharing his knowledge of the plants and animals. The variety of trees and flowers seemed unending, and it became important to me to learn their names, just as one knows family and friends.

Throughout this childhood, my immediate family -- I mean my mother, father, brother and sisters -- was as essential as the book, the woods, and my friends. They tolerated the nature collections in the bedrooms, allowed me to explore and play in the woods without adult supervision, and supported my appreciation of nature with a backyard garden, frequent picnics, and weeks at a summer camp.

Actually, they were teaching me more than love of nature. From them I was absorbing a love of people and a love of peace. My mother, Kentucky born and bred, had been deeply affected by the legacies of the Civil War, where, in Kentucky especially, one relative was so often pit against another relative. She also knew race relations from both southern and northern perspectives, and she had close-up knowledge of rural poverty. Without using the word "liberation," she was a strong advocate of liberating women from the necessity of filling only traditional roles. She was among those who established the first Maternal Health Clinic (now Planned Parenthood) in northern Ohio, and was elated when our local school board finally was forced to reverse its longstanding policy of dismissing women school teachers when they became married.

My Pop (everybody called him "Pop"!) had been sent off to a military school as a boy, and from this experience gained a deep aversion to militarism. Whereas my Mother earned a master's degree, Pop never finished college. However, he used his remarkable organizing abilities for good causes, breaking ground with the community chest idea and the Easter Seal Society. More than that, he was simply one of the kindest individuals anyone could find. So many times Mom would say, "Pop would give you the shirt off his back."

Ours was not a Quaker family, and I can hardly recall my parents ever attending church, but their life experiences led them to create a family that loved peace and advocated peace. It was no wonder that their sons became conscientious objectors in World War II.

My parents were verbal people and often spoke about important values, but among us four children I was, by illness, especially fortunate in being able to talk with them. At age 13 1 had the bad luck, or good luck, depending on how you view it, of contracting rheumatic fever. That was before the knowledge of penicillin's good works. Simple bed rest was the prescribed treatment, so that I spent nine months in bed and a year out of school, which gave me much time with my parents.

After the first few weeks of illness it is easy for boyhood friends to forget to visit. Childhood is a time for action -- hiking in the woods, playing softball, riding bikes -- not a time for lengthy conversations with one who can't share the action. My brother and sisters had gone off to college, so conversations were mostly with my parents, and aloneness was a major part of my daily routine. I think it was good that television was not yet on the market. The radio occupied some time, but I remember mostly reading and thinking -- and looking out my second story bedroom window. My hospital bed mattress was as high as the window sill, permitting me not only to see unobstructed over all the neighborhood yards, but also to fairly hang out the window, which was always screenless.

With hours to spend in observation from one viewpoint, I became aware of things in nature that I had never noticed before -- the grackles feeding on the pin oak acorns, the neighbor's cat springing to capture a scolding house sparrow, a blue jay flying into the honeysuckle vine beneath my window, with an egg speared on its beak, the spring migration of warblers ... and always my friend crows wheeling and cawing over my woods a block away, as though they were a "forest patrol" letting me know it was still safe there.

This was a time for meditation and deep thinking like I had not known before. Life and death issues became deeply important to me as I observed the flow of creation outside my window and considered this unexpected turn in my own life. How long would this young boy live? What kind of life would he have while he lived? What would death be like? Would it be different for him than for the sparrow in the mouth of the cat or the egg on the beak of the blue jay? At the time I knew nothing about Quakers, but later I came to realize that I was experiencing Quaker worship -- and I have always been grateful for it.

All of these experiences led to the next major influence in my relations with the universe, a summer spent as a volunteer nature counselor at Hiram House Camp, near Cleveland. I had just finished my junior year at high school, eager to learn, and enthusiastic about helping others to love nature.

What a miracle that summer was! There are camps and there are camps, but this one was one of the most nurturing, wonderful places one could imagine. Operated by a progressive social agency, it was coeducational, served a broad spectrum of ethnic groups, ages, and economic levels, and was staffed by a talented, idealistic group of college students under the leadership of one of the most Quakerly women I have ever known (though I never did know if she had any church affiliation.) Its program focused on small-group living in a natural setting.

Here I met and came to love a new natural ecosystem, the beech-sugar maple climax forest. Here I met my best friend, a Sicilian-American youth from the slums of Cleveland, with whom I would share 20 years of camping and teaching experience. And here I met Alice, a vivacious camper who loved nature and people as I did.

Alice and I returned to camp year after year, with our love for each other maturing along with our bodies and minds. As Quakers, you probably will he interested in knowing that we participated (along with the other camp staff members) in our first Quaker-type worship together at the end of World War II, in the evening of August 14, 1945. There was not an "official" Quaker among us, but a woman counselor from Oberlin College suggested that a Quaker-style, candlelight worship service would be the most appropriate way to celebrate the end of the war. Early in 1951, Alice and I joined the Cleveland Meeting of the Religious Society of Friends and that June married each other in a sunny, sloping field scattered with young trees, "in the presence of God and these our Friends."

These early years, of course, were the most formative years of my life. This was when I was learning to love, and this was when I was beginning to see the unity of the universe. Going into my first summer at camp, the universe of which I was conscious was more or less equated with nature. When I finished that summer my universe included, as well, a rich diversity of human types. Ten weeks of working and playing with, of loving. African- Americans, Mexican-Americans, and all kinds of European-Americans could not do otherwise. A year later I entered the University of Arizona to study both sociology and ecology.

To be sure, later experiences contributed their share to my world view. College life, extensive travel and trip camping, work experience with the American Friends Service Committee in Mexico and Peru, teaching diverse students in diverse settings, from a well-to-do suburb of Cleveland to a metropolitan university in Chicago and a mountain hollow in eastern Kentucky, and our last two decades of life on a northern Illinois farm -- all these played important roles. Our own three children taught, and still teach, us much about loving the universe -- more than they know. But the truth is that the foundation and rough framework for my belief system had all been completed by the time I left high school.

Nonetheless, absorbing the full meaning of the universe took some time! Notice the derivation of the term from the Latin unus meaning one and vertere or versum, meaning to turn, that is, "turned into one whole." Or in the popular language of ecology: "everything is connected to everything else." Everything is one thing, a whole.

You recall my desire to learn the names of all the trees and flowers, assuming that they are all discrete species. One summer at camp a botanist friend was helping me learn some of the more difficult-to-identify wild flowers. Imagine my frustration when he refused to state with certainty that a particular flower was this or that, that it was probably a hybrid or intergrade between two species. In retrospect, I should not have been so perplexed because from my anthropology professor I had already absorbed the truth that there was no such thing as a "pure race". They all intergrade into one another. Why not the same with plants?

Now I understand that it is we humans who, for the sake of communication, divide one thing from one another with our labels. Language is basic to human society, and labels are necessary for communication, of course. The danger is that in doting on our verbal ability we forget that these words are only symbols that approximate reality. In fact, I have come to believe that all classification, all categorization, is ultimately arbitrary, as labels are placed at varying points along a spectrum.

The Religious Society of Friends has done a good job of putting symbolism and ritualism in their proper places, at least as far as religion and human society are concerned. Now I believe that our Religious Society has another important purpose: to help us see, help us know, help us remember that all of us -- earth, sky, water, plants, animals, people -- all of us -- all of us who have come before and all of us who will come in the future, in spite of our separate labels, are one whole, one universe -- united not only by the ecologists' biogeochemical cycles and energy exchange, but also by that positive, creative power, which we call variously the Inner Light, Love, or God.

So the first principle in loving the universe is to understand its unity. When I find it very convenient to use labels that separate me from you, or us from them, my better self tells me "watch out," "remember, you are they." I have some of you in me, and you have some of me in you. Untold generations are distilled into our beings of today. It is interesting to me that the sciences, the arts, and religion unite in defining, and refining our understanding of, this oneness -- this unity of the universe.

For example, an artist with words, John Donne wrote, "No man is an island, entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main..." The scientists with mechanistic methodology are merely exploring the details and ramifications of this oneness, defining more precisely the ways in which we are "part of the main". And our religion uncovers the deeper spiritual unity of the whole. In this case, contemporary religious insight makes us aware that the masculine symbol "man" is a separating symbol when we are talking about a species, that happens to have two sexes.

Recently, at the Milwaukee Zoo, I observed our marvelous relatives, the primate apes, and read a label that showed the tree of evolution. I ask myself, if I believe in evolution, which I do, and if I believe in the "Inner Light", which I do, how can I deny that bit of light in my animal relatives, in my plant relatives, and even in the lifeless elements from which life arises? Did not God, the Love Spirit, the Creative Spirit create all, and is not some of that spirit in all?

For me the spirit of love is the creative force that permeates all the universe to some degree. It is the positive side of a spectrum that grades into hate at the other end. The ends of that spectrum have been given other labels: good-bad; violence-nonviolence; war-peace; God-Devil; and so on. We all have within us varying amounts of each end of the spectrum, and a central purpose of our Religious Society is to recognize, enhance, and use that positive force within us, what we call that of God within us -- or the Inner Light.

Granted all of this, how do I love the universe? One thing I try not to do is to make counter-productive or futile attempts at using labels. For example, believing in the stream of life and creation, I find it useless to argue about whether life begins with the egg, or the sperm, or the union of the egg and sperm, or on some arbitrary time period after that union. An African- American once taught me how counter-productive the labeling of people can be. Though one of my best friends, we periodically engaged in angry words. Finally I understood that this happened when, with all good intentions, I initiated discussions about black-white civil rights issues. My racial labels separated us. Being a slow learner, I guess, I later had to get the same lesson from a woman in connection with gender labels.

To take another example, while we need to know something about the changing status of minority groups in our society, I sometimes fear that, with all good intentions, the social scientists may be engaging in counter productive use of labels in their studies. Thus, by asking about, reporting, and projecting census figures on the number of Hispanics in our country, they may be making us Anglos more conscious of and more separated from them. How much of a given ethnic background qualifies us for a given label? With the amount of ethnic mixing taking place in the United States, how can we possibly make meaningful projections of the Hispanic population to the year 2050? I am one-fourth Scot, and I thrill to the sound of bagpipes, but no census-taker asks me about that.

I mention the bagpipes to lead into my next principle. For me, a fundamental way to love the universe is to recognize and appreciate diversity. (I learned that beautiful phrase, "recognition and appreciation of diversity" at the Friends General Conference Gathering at Carleton College, from a religion professor who taught a course by that name there.) There is a fundamental difference between using labels in a rigid and separating manner on the one hand, and recognizing, appreciating, and even preserving the wonderful diversity which the labels try to reflect. Thus, Scotch bagpipe music is exciting, stirring and deserving of preservation, but one does not need to be of Scot origin to appreciate or play the bagpipes.

I like the reverie that George Catlin, the painter of Native Americans, had early in the 19th Century. In his vision he saw a great national park which would preserve both the bison herd of the Great Plains and the Native Americans who used the bison as the basis of their culture. The same idea has become the basis for the organization Cultural Survival, which works to save, simultaneously, indigenous cultures and the natural ecosystems on which their cultures are dependent. I like that, as long as individuals are left free to pursue their own interests. I would not appreciate being told that because I grew up in a small town in Ohio I could not partake of life in Chicago, or in a Kentucky mountain hollow, or in a South American city. (Incidentally, let us not think that "diversity of the universe" contradicts the "unity of the universe." Think of a rainbow with its diverse colors.)

Loving and preserving diversity is synonymous, then, with loving the universe. Again, it is simple: the universe has diverse parts; therefore we must love diversity. I will not argue that we must save all species of life and all natural ecosystems because of their potential benefits to humans. Others make that case very well. In fact, ecologists talk about the survival value of diversity, the concept that diverse ecosystems are more stable than those with less diversity. However, it seems to me that for Quakers, preserving the natural diversity of the universe is merely an extension of the Quaker belief in "that of God in all people". There is that of God in all things, and so I must love all things.

In addition to using labels constructively instead of divisively, how else do I love all things? Am I a vegetarian? Do I not swat mosquitoes? Do I stop using rain forest products? One does not love the universe easily.

When I registered as a conscientious objector to war I stated that I could not serve even in a noncombatant position such as the Medical Corps, because I saw that such personnel were essentially supporting the man who pulled the trigger. The person who pays the taxes also provides essential help to the person who drops the bomb, but it took me longer to become a tax resister. Dealing with the natural world is even more complex. I don't hunt animals for sport, but I use electricity generated by burning coal, the mining of which destroys whole mountain tops that used to harbor wildlife. I drive my car to Illinois Yearly Meeting using gasoline, the production of which results in spills that foul the water and the refining of which produces pollutants that foul the air.

The truth is that all life is at the expense of other life. The predator has its prey, and the sugar maple shades out the oak. Life and death are labels for the ends of another spectrum, and it is difficult to be a consistent absolutist on life and death issues. I do not know how I can avoid killing something, at least indirectly.

However, I have learned that I can control the nature of my killing and the amount of my killing, and to that extent love the universe more fully. For one thing, I can rid myself of the joy of killing. Think of the gradations along this spectrum. I am a conscientious objector to killing other humans. I have killed chickens for food, but did not enjoy it. (If I am willing to eat a chicken, should I not be willing to kill it?) I do not engage in hunting or fishing for sport, but where wildlife populations increase in the absence of natural predators I see the need to control them at times. I might as well rip rare wild flowers from the ground with my own hands as to refuse any controls on a swelling deer population. The restoration of native prairie vegetation in northern Illinois invariably calls for removal, that is, killing, of alien species, such as the European buckthorn. I remember one enthusiastic prairie restorer gleefully shouting "Kill, kill, kill!" as he sawed away at some buckthorn. I think the Native Americans had a better way of killing, even plants, which recognized the spiritual nature of the universe and demonstrated a love for the universe.

To control the amount of killing -- or to use a more polite expression, to control the amount of environmental damage -- at my hands, I have found the greatest help in a longstanding Quaker testimony, that of simplicity. In this context I am referring particularly to simplicity in our consumption of material goods. In trying to live life with simplicity I find both joy and challenge. The joy comes from knowing that each thing that I do without permits some other life to blossom, either now or in the future. The challenge comes in selecting that next thing which I can do without. I will not recount my successes, nor my failures, in my efforts to live Quaker simplicity. (The little booklet by Jack Phillips, titled Walking Gently on the Earth, contains good suggestions for those who welcome some.) Suffice it to say, that my observations are that most Quakers today are like myself, in giving more lip service than practice to Quaker material simplicity. Thoughtfully practiced simplicity, I think, is the hope for the sustainable development envisioned at the recent Earth Summit meetings held in Brazil.

Another discovery which I would like to share is that there is a difference between personal simplicity and ecosystem simplicity. It may save me time, and seem simple: to throw my solid waste in one trash can, rather than recycle: to turn up a thermostat, rather than to put on a sweater or open and close solar shutters: to drive my car, rather than hassle with public transportation. Though these actions may bring greater simplicity to my harried life, they may cause disastrously complex interactions in the global ecosystem. Loving the universe today calls for consideration of the ecosystem impacts of personal simplicity.

In conclusion, then, I believe that loving the universe is the central challenge for our Religious Society, as it is for this whole intelligent species of ours. It is necessary if this universe of ours is to endure as we know it. It is necessary, I believe, because there is that of God in all Creation. Religious people have an obligation to point out the spiritual connections within the universe.

Three principles will help us love the universe better. The first principle is that of the unity of the universe. Our labels would leave us to assume that human society and the natural environment are separate from one another, but in reality we are one whole. Lasting solutions for social problems and environmental problems are dependent upon one another.

The second principle is that of appreciation of diversity -- diverse cultures, diverse species, diverse ecosystems. If we appreciate and save all the parts we will certainly save the whole.

The third principle is that of simplicity, particularly as it applies to levels of material consumption.

From these derive the specific practices that suit each of us individually. Appreciation of diversity means that some of us will work to restore native American ecosystems, like tall-grass prairies or oak savannas, while others will help the sustainable development of indigenous people. Consuming less in a simple, low-impact lifestyle will allow some to share resources rightfully with others in the world and permit others to give time and energy toward helping to solve social and environmental problems.

§I remember learning to walk the paths at camp at night without a light, save for the faint glow of the sky in openings above our heads. The firm packed soil under our feet told us we were on the trail, and we learned to talk with the barred owls that shared the beautiful night with us, as the crows had shared the day. We were people of diverse backgrounds learning to love one another, the owls, the woods, and the dark. It was a good lesson in loving the universe, especially for us who talk so much about the Light.

Thanks for letting me share with you some of the paths of my life and the destination to which they have led me.

IYM Home | About IYM | Calendar | Member Meetings | Publications | Search