Creativity and Spirituality

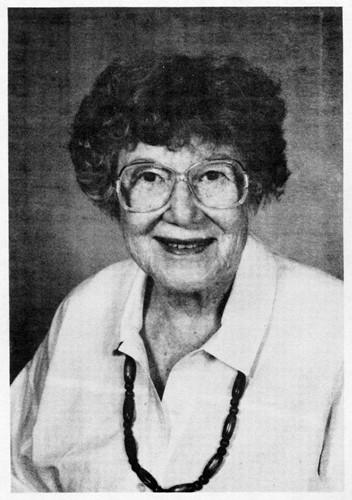

Mary Fyfe

The 1990 Jonathan Plummer Lecture

Presented at

Illinois Yearly Meeting

of the

Religious Society of Friends

McNabb, Illinois

August 4, 1990

Introduction of Mary Fyfe by Paul Landskroener

Mary Fyfe is a remarkable woman. No single introduction of her can begin to fully acquaint you to her many talents, gifts, interests, and experiences. The committee that invited Mary to deliver the Jonathan Plummer Lecture this morning knew that she was a woman of substance, of depth, and with something to say. I would simply like to sketch in a few words some aspects of the life that we have come to know as Mary Fyfe.

Mary was born in 1914, the youngest of four children, to a Presbyterian family in Macomb, Illinois. Her father was a farmer, and her family raised most of their own food on their farm.

Mary received her Bachelor of Arts degree from Western Illinois University and her Masters and Doctor of Philosophy degrees from the University of Chicago.

Mary's professional life has been as an educator. She taught children in one room schools in McDonough County, Illinois, for 9 years. She then became Superintendent of the McHenry County Schools and oversaw the consolidation of four large rural townships into one of the first consolidated school districts in Illinois. This latter achievement received national and international attention as an example of democracy in action and of community involvement in decision-making.

After receiving her doctorate, Mary started and developed the elementary teacher training program at Purdue University. She spent one year at the University of the Punjab, Pakistan, developing teacher training programs, and two years in Nigeria developing in-service teacher training for 26,000 young Nigerian teachers. She later returned to Purdue and taught early childhood development and directed the Purdue Educational Research Center. She then served as Vice President for Academic Affairs at Governors State University in University Park, Illinois.

While at Purdue, Mary spent considerable time developing parent and early childhood education programs in Afro-American communities in Bolivar County, Mississippi; Atlanta, Georgia; Lafayette, Indiana; and Cleveland, Ohio.

Mary came to the Religious Society of Friends from a not uncommon route: the Unitarian Church. Finding the Unitarians in the south suburbs lacking a sufficient service orientation, Mary began to attend Thorn Creek Meeting in Park Forest. She joined that Meeting and was married under its care to Bill Fyfe in 1984.

After marrying Bill, Mary moved once again to McHenry County where she has served McHenry County Friends Meeting as Clerk and in many other capacities, official and unofficial. Since attending IYM for the first time in 1984 to hear James Garrettson's Plummer Lecture, she has also rendered considerable service to Illinois Yearly Meeting.

Being invited to deliver the Jonathan Plummer Lecture is perhaps the highest method of recognizing the spiritual gifts of a member of Illinois Yearly Meeting. But it is a peculiar sort of honor in that it requires a considerable commitment of time, thought, and energy to complete. Little did the Program Committee know last fall when we issued the invitation that the next year would require a large measure of Mary's time and devotion helping Bill overcome a serious illness. True to form, however, Mary reported to me several weeks ago that the lecture was completed, despite this unforeseen burden. Not only that, but she says she has finally found the time to do some weaving. She has recently completed eight rugs and fourteen pillows and is about to begin a blanket for a double bed. So if I had felt a little guilty about laying the responsibility for the Plummer Lecture on Mary, I don't any more. I look forward to her weaving us all together in the next hour with her lecture, "Creativity and Spirituality."

Creativity and Spirituality

This monologue began when I accepted an invitation to give (produce) the Plummer lecture. I have written this out of a feeling for a process and a feeling for a commitment to it. I speak to and from a diverse fellowship: poets, philosophers, craft persons, farmers, housewives, artists, students, teachers, anarchists, community members, social beings with black, red and pale faces.

This article has a plan. There are passages of development -- also of inquiry. What I want to say here is about love and peace and wholeness and freedom and wisdom and trust and the purpose that the native American gives us, "that the people may live." Because I am a teacher, I am interested in search and growth, children, young people and adults, schools and community, our country and the world.

I feel the need to look back into my life, personal and professional, to identify the awareness, self discovery and understanding of creation-centered spirituality. Remembering can be both pleasant and not so pleasant. I will give you samples of each.

I began teaching in a one-room school where about 30 children were in attendance in grades one through eight. I was eighteen years old and had had two years of work at Western Illinois State Teacher's College, and I had studied a book entitled: The State of Illinois Course of Study, Grades 1-8. Besides, along with my brothers and sister, I had myself attended one-room schools. I wanted to be a teacher -- a good teacher -- more than anything else. That first day finally came. With that Course of Study beside me, I was ready. Those of you who have had similar expectations and experiences can imagine quite accurately what took place. Not a child -- not one -- knew what I was talking about when I "used" the materials and assignments listed under "September, Week 1." So I tried turning back in the Course of Study to use the guides for what they should have covered late in the previous year. But, alas! that also seemed unknown and untried.

We were getting to know each other and were becoming friends. We had wonderful times on the playground and doing things together in the classroom, such as telling stories, singing, making the schoolroom attractive, identifying trees and wild flowers. But alas! No book learning! By the end of the first week, I made a trip to talk with the County Superintendent to tell her about my problem. By this time, I was sure that the children had not had a very good teacher the previous year, and that the Superintendent would help me deal with that.

And that she did! I have forgotten to relate to you that the County Superintendent was my father's cousin and had watched me grow up. In fact, I believe she doubted that I had grown up. She spoke sharply to me about all teachers doing the best they can, that children forget over the summer and need help in recalling previous learnings, and that I must work hard. I can't remember that she gave me any encouragement or real help with the teaching process. It is quite possible that she did because she was a thoughtful and kind person. I was simply devastated by the situation. But I still had the burning desire to teach, and realized that I was on my own to make that happen.

Let me summarize some of the things which occurred. Right away, I became a keen observer of the children. Among the little ones, I noticed that the children who were friendlier, healthier, and more independent also were better students. I noticed the children in first grade who were losing their baby teeth were able to read earlier. The happy outgoing children did their work better and without delay. I became aware that children who had adequate and balanced lunches listened well and concentrated longer on their school tasks.

I remember a young day-dreamer, a boy about 9 or 10, who simply wasn't with us -- unless he was teasing or shoving or quarreling angrily with someone. He had no friends at school. He was always chosen last in any game. Then one day for the first time he hit a ball when he was up to bat. Everyone cheered. That afternoon he was a model cooperative student. His physical coordination, his social behavior, and his school work continued to improve from that day forward. He easily made friends with others.

I learned that if I linked each assignment from the Course of Study with something in the personal lives of the students or with their previous learnings, their study efforts, written materials, and class discussions were much improved. Learning new things became pleasant and attainable.

I also learned about individual differences. Some children not only learned more easily, they learned at a faster rate. Often these children helped others learn. They became assistants working with other children under my supervision.

Miss McGaughey came to visit our school during the fourth week of September, giving us much praise, a wonderful occasion for all of us. She never mentioned my visit with her during the first week; nor did I. am amazed at the teacher I am and can be when I am true to my journey. I believe my ability to teach evolved spiritually and creatively.

As time went on, it became very clear that the children and 1 needed parents to be involved with us in the educational process. For the child, the parent, and for me, it was so much easier for all if we operated as a team. It was apparent that if a child was not getting along well at school socially or academically, the parent knew about it, wanted help, wanted to help, and deserved to be involved. On the other hand, the parent of the child who learns easily and has many gifts appreciated a closeness with those of us at the school.

Can you remember that story going around recently entitled "All I Need To Know In Life I Learned In Kindergarten?" Well, much of what I needed to learn about teaching I learned as a beginning teacher. True, I believe I continued to grow in skills and understanding as my teaching opportunities expanded to the university level, to settings outside educational institutions, and to international assignments. I am aware now, perhaps because I am writing this paper, that from that first year forward the curriculum and instruction grew out of the needs of individuals and resources available. I also learned that involved individuals assisted in the planning, and took responsibility for outcomes regardless of age, color, previous learnings or background.

I continued to teach in rural elementary schools for 11 years, the last two in McHenry County, where I was appointed County Superintendent. I found that working with teachers, however different on the surface, was similar to teaching. Teachers liked meeting in groups with other teachers, identifying problems, selecting materials, and making decisions important to them. For me, it was teaching on a different level.

Early after I became County Superintendent, a young man came to talk about education for young children. I was thrilled to have a parent initiate an interview to talk about early education for children living in rural areas. After an hour or more of stimulating conversation, we agreed that we had to have a group of five-year-old children together in one place in order to have the kind of education which we thought appropriate. This led us to thinking about how to go about doing just that. I asked him the age of his children. He said, "We have only one child, six months old." My friend's name was Bill Fyfe; his oldest son, Beye, is now 47 years old.

My new friend agreed to get persons from his own district and two neighboring districts to meet for discussion. I agreed to assist in every way possible. We met and discussed many things: available teachers, tax rates, as well as adequate programs for young children. Parents were gravely concerned about their children riding to school on buses. As we adjourned, we set a date for the next meeting. At that meeting there were representatives from seven one-room school districts -- and so it went for the next few months.

The children were attending one-room schoolhouses with pot-bellied stoves, outside pumps and outside toilets. The separate schools were not only inefficient but were burdensome to maintain and to staff. However, it took much wrangling and bitter arguments to work through the problem. I remember on one occasion the farmers were accused of housing their cows better than their children.

Finally, 23 small districts came together as Rural Consolidated District 10, Woodstock, Illinois, and I was asked to be the first Superintendent. Using the community school concept, the curriculum and instruction grew out of community needs and the utilization of resources found within the neighborhoods and beyond. New education guides were developed, in-service programs organized, and new buildings planned. We worked with the adults, parents and non-parents, in such a way that schools became central to the community. We were all partners in the education of the children.

Tempting as it is to tell you in some detail about the results of the consolidation, I must refrain as it is outside the scope of this paper. Stories about our schools were published in periodicals, books, and even in a documentary film. Was I creative? Yes, I was. Was I spiritual? Yes, indeed. I ministered lovingly and long to the children, their teachers, the parents, and the community. And overwhelming caring, concern and joy were given back to me.

Next stop was Purdue University, where I remained for 17 years except when on leave for assignments in Pakistan and Nigeria. I was in Nigeria when President Kennedy was assassinated. I was appalled during the long hot summer when water hoses and police dogs were turned on children who were marching in Alabama, and three young civil rights activists were killed in Mississippi. Alone in the bush of Nigeria, I asked myself, "What am I doing in Africa? The problems of black communities at home are challenging enough." Upon returning to Purdue, I took advantage of the University's liberal policy for outside consulting along with my regular job. Assignments resulted that took me to black rural Mississippi for the Head Start Programs, the Parent and Child Center in the black, urban Hough area of Cleveland, the Urban Education Laboratory in Atlanta, and the black community of Lafayette, Indiana. Looking back, I realize that great care and concern for my well being was extended so generously by the black people with whom I lived and worked in this country and in Nigeria. I am grateful.

My last academic position was Vice President for Academic Affairs at Governor's State University, where 40% of the students were African Americans.

During the 32 years I was working in administrative positions, I taught at least one class each session. Teaching remained satisfying and fulfilling.

I hope I have made it clear to you that all I learned that first year of teaching was lived and extended over and over again in each assignment of my professional life. As a result I have enjoyed wonderful experiences literally all over the world as others gave to me their gifts of caring, support, cooperation, wisdom, love, and trust. I retired after 43 good years.

§

I have thought and read about this topic for a very long time. The words creativity and spirituality are often used, but seldom clearly defined. They remain elusive, mysterious, beyond experience. I wish to present excerpts from a number of writers on this subject.

According to the psychologist Carl Rogers in Toward a Theory of Creativity, there are three characteristics a creative person must have: an openness to and an awareness of experience; a self-reliant, independent approach to finding solutions; and a flexible, even playful attitude toward manipulating concepts and ideas.

What we consider "familiar" is based on our past experience. The artist helps us to see the world we have always known, in a completely different way: making the strange familiar and the familiar seem strange. There are many people who prefer not being jolted into new ways of experiencing. The creative person thrives on ideas and visions which change forever their previous notions. The world is hungry for creative expressions of the spirit. Within each person lies creative and spiritual energy.

Today, we find ourselves in the midst of perhaps the most perilous times ever. Some would say there is little in our culture to encourage either creativity or the spiritual life. We have few choices: either we allow a creative reverence be expressed through us, or we destroy those we love and our earth. We must all become artists; we must all become engaged in creative activity and with the source of our being. This implies a spiritual approach. Edgar Mitchell, the astronaut, points out the difference between religion and spirituality.

|

Religion is what we believe because someone else experienced it. Spirituality is what we believe because we have experienced it ourselves. |

A present day spokesperson for the spiritual connection with artistic activity is Matthew Fox, a Dominican priest, who has been writing, speaking, and conducting workshops on this subject for at least the past ten years. Fox speaks of the importance of the artistic experience:

| In the work of the artist, subject/object distinctions are broken through, and we experience the unity of all creation once again. Healing takes place; a healing between us and the Creator and between us and creation and between our deepest inner self and our outer self. |

Fox affirms our need to get back in touch with the source of richness that lies within each of us. When creative persons reach into their depths and bring forth things genuine -- a song, a piece of pottery, an idea, a relationship -- a union is formed between people and the Creator. This can be called a spiritual experience, and it truly is.

In his book, Original Blessing, Fox has an appendix entitled: "Toward a Family Tree of Creation-Centered Spirituality." He explains that he has used the word "toward" in the title because he believes the list is by no means complete. Beginning with Jesus and extending through the nineteenth century, he has devised a code of stars which indicates the fullness in teaching and living out creation-centered spirituality. His method is similar to our system of using 5 stars, 4 stars, and so on to signify our assessment of restaurants or bed and breakfasts. While he has ranked several hundred, I have chosen to share with you the top five:

| Jesus Christ | 5 stars |

| Hildegarde of Bingen (1098 - 1179) | 4 stars |

| Francis of Assisi (1181 - 1225) | 5 stars |

| Meister Eckhart (1260 - 1329) | 4 stars |

| George Fox (1624 - 1677) | 3.5 stars |

There were several other Quakers in his list.

Look back at high points in your life. They usually come when we discard something and take a step forward. Sometimes there is pain associated with this step forward because we don't want to leave something behind, but usually when we do, we grow. With each new awakening we discard some cherished viewpoint or reintegrate it into a larger outlook. This is the creative process.

Like any work of art, this is an individual process that comes from within. Since the creative process is so closely linked with the spiritual, this makes for transpersonal development. Lois Robbins in her book, Waking Up in the Age of Creativity, suggests some attitudes and actions that nourish creation spirituality:

| Accept yourself. Since you are indeed created in the image of God, you have the freedom to create just as God has, and the right to a playful relationship with the world. |

Be brave. Fear is the greatest block to creativity, yet it is inherent in the new and unknown. Wrestle with your fear, but respect it. You can learn a lot from observing what scares you.

Cultivate "beginner's mind." Keep learning, especially in the field in which you feel most competent. This keeps you open to not only your new insights, but to the discoveries of others in a rapidly changing world. This is why it's so important to be creative rather than learning to retain facts. The facts are always changing, but creativity has an integrity of its own.

Become an acute observer. Look for similarities, differences, and distinguishing characteristics in whatever you are dealing with. When you do this you are exercising both the rational and intuitive sides of your brain. You are also accepting your responsibility to be all you can be by being as awake as you can, both to your inner wisdom and to your environment. Try many different combinations of association and relationship. Divergent thinking is just as important as its opposite, congruent linear concentration. It is far ranging rather than focused, making intuitive rather than logical connections.

Keep asking questions. Then ask questions beneath the questions. Keep your mind curious and your doubts alive. Be puzzled. Encourage a sense of wonder.

Carry a notebook with you wherever you go. Capture in it your hunches, strange thoughts, "silly" questions, and inspirations before they fly away.

Develop a meditative creative discipline. Doing things with your hands develops self esteem, and doing them with awareness increases self-knowledge and compassion as well as creativity.

Find ways to teach others what you know or are learning. Teaching is the best way to learn.

Laugh. Humor releases tension, helps put problems in perspective, and sets the stage for the playful attitude in which creativity begins to flow. Any spirituality which cannot laugh at itself is based on fear.

Read widely in areas other than your own field and try to relate what you learn to what you already know. Cross fertilization is helped by the absorption of seemingly unrelated knowledge.

Avoid rigidly set patterns and ways of doing things. Be willing to try new things, to take risks, and to fail. Be flexible enough to let one idea go in favor of another.

Learn to live with ambiguity. Both creative and spiritual breakthrough are born out of that discomfort.

While preparing for this presentation, a friend loaned me the book This Way Day Break Comes by Annie Cheatham and Mary Clare Powell. If you have any doubt that indeed women are changing society, read this book. Cheatham and Powell heard the stories of almost 1,000 women as they spent four years traveling 30,000 miles around the United States and Canada. Many books and articles accurately report the hardships and injustices under which women live. But This Way Day Break Comes affirms the efforts of a thousand women who are involved in changing ways they relate to each other, who are creating physical spaces they need, and who pursue world peace.

|

Louise is a builder. Because I had such an open background, intellectually and psychically, I learned early to trust the wise woman inside, or the God part of me, and I have experienced it all my life. I can't always tell how things come to me, but there is something utterly natural and very compelling about my inner process.... Starhawk dreams of world peace, and she uses her inner power and wisdom to work for it. She asks the question, How do we shape a society based on the principle of power-from-within? Power-from-within has many names -- spirit, Goddess, eminence -- God. Sr. Marian, president of the Sisters of Loretto said, Art is an encounter. It involves people in a whole way. Social activists try to change peoples' mentality and values by organ educating, and talking to them. But we are not changing them. It takes artists to change peoples' minds about South America, or hopes for peace, or global awareness. Art making requires a faith stance. |

Perhaps some of you read Lear's magazine. It is a fairly new periodical advertised as being "for the woman who wasn't born yesterday." I sent in a charter subscription when it first came out, but I found I was put-off by its "slickness" and dropped it after the first year. Then I missed it; I realized there was always at least one very good article in each issue. I became a subscriber again.

Just after I had begun thinking about this lecture, there was a very good article in the December 1989 issue titled "Making the Spiritual Connections." Seventeen well known persons, including ministers, writers, psychiatrists, professors, politicians, and others, attempt to define the elusive reality of "What is spirituality?" Here are excerpts from the answers given by four of the seventeen persons.

John Updike, novelist, essayist:

| Pressed, I would define spirituality as the shadow of light humanity casts as it moves through the darkness of everything that can be explained. I think of Buddha's smile and Einstein's halo of hair. I think of birthday parties. I think of common politeness, and the quixotic impulse to imagine what someone else is feeling. I think of spirit lamps. |

Faye Wattleton, President, Planned Parenthood Federation of America:

| Spirituality sings in each of us. It is the zest of life. It just is. My own spirituality is deeply rooted in a religious ethos. It shapes my vision of the world as it is and as it can be. It has forced me to grow humble as I have grown mature. It opens my mind to the magnitude of life -- the insignificance of each of us as individuals but the enormously profound power of the human family. |

Robert Coles, Professor of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School:

| Here are the thoughts of an 11-year-old girl: "I think you're spiritual if you can escape from yourself a little and think of what's good for everyone, not just you, and if you can reach out and be a good person -- I mean live like a good person. You're not spiritual if you just talk spiritual and there's no action. You're a fake if that's what you do. But if you try to live up to all you hear in church, and if you think of your neighbors and friends, and the people who are in trouble and need help, and if you try to give them some help, then you're on your way to being spiritual, I think." I think so too. |

William Sloane Coffin, President, Sane/Freeze Campaign for Global Security:

| Spirituality is what people do with their freedom, for freedom is so much more than freedom of choice. In earlier times the word was practically synonymous with virtue. When Abraham Lincoln called for "a rebirth of freedom," he didn't mean the freedom to exploit, to squander, to dissipate. People were truly free only when they could open their minds to truth, their consciences to justice, and their hearts to love. So we can define a deeply spiritual person as one truly free. |

§

For a very long time I yearned to learn to weave. The realization that weaving takes a commitment of time and effort prompted me to defer that activity until retirement. So with eagerness, some timidity, and clumsy fingers, I enrolled in a weaving class. It was exciting. The process was interesting; the weavers were talented and artistic; I saw textures and colors in a new way. I was a slow learner in weaving, but I loved it.

Yarns with stubby textures and exotic colors were hard to come by in the south suburbs where I lived. After having to drive 25 to 40 miles to purchase the kinds of yarn I wanted, I decided to open a fiber arts store. So with a little study, a self-made market survey, and the advice of small business consultants, I opened a shop. We offered materials, equipment and classes in stitchery, knitting, quilting, basketry, spinning, and weaving. Business was good; customers were pleasant. But again I had no time to weave. For seven years I operated the business until it became just too energy and time consuming. So I sold it -- intending to return to weaving seriously.

But before I could get that done, that nice young man who came to talk with me about education of young children, in 1945, invited me to share his life with him at The Rise in Woodstock. How interesting it was to return to an area where I had lived thirty years previously. Being a part of a loving family which I had known for many years, returning to my roots planted in country living, participating in the life of wonderful McHenry County Meeting and wider Quaker groups, having time for reading, gardening, stitching, traveling -- life was good in 1984.

Two years later, depression hit. I have always felt the ups and downs that all of you have felt -- sadness at the loss of a family member or close friend, disappointment with myself for not going the extra mile, loneliness for someone not present. But this was different from sadness or disappointment. I felt utter black despair, a feeling of being cut off from everyone, lacking hope for the future, powerless to change. And it was all my fault! I sought help. Two messages I received from my psychiatrist during the first visit are indelibly etched in my mind: "1. Depression is a disease, and it can be cured. 2. I believe (my doctor said) that you have experienced emotional and psychological abuse, and after hearing about your work, I believe it was by men."

My psychiatrist, a young British woman, had worked with Dr. Aaron Beck, founder of The Center for Cognitive Therapy at the University of Pennsylvania. Beck's research led him to conclude that depression is a disturbance in cognition -- thinking, in other words. The person who is depressed thinks in negative ways about self, environment, and the future. This pessimism affects the person's disposition, ability to set goals, and relationships. My doctor used Cognitive Therapy, which literally trained me to look and interpret things differently. This helped me to feel better and to act more productively. I worked closely with my doctor for almost two years. While recognizing the advances made in the development of pharmaceutical antidepressants, we were both pleased not to use them.

I want to speak briefly about the second comment made by my doctor, "that I had been abused emotionally and psychologically by men...." I believe what she said is true, but I would never have dared to put it into words. I worked in educational administration for 32 years, where almost all my colleagues were male. Unfortunately, if I were beginning over today in that field, I would expect to find much the same conditions. While many of those men were competent, supporting, understanding, and friendly, unfortunately, some were uncomfortable, unsupporting, and unfriendly. They were often incompetent and clumsy, much like the little boy who couldn't hit the ball when up to bat. I felt anger and abuse directed to me personally, but I did nothing about it. I did not confront my anger, and I did not confront the powerlessness that accompanies it. To understand the source of abuse is helpful. My belief that there is some of God in every person is helpful. I avoid self-pity, try not to bottle up anger, and try to increase efforts to empower the powerless to speak. I yet have trouble with forgiveness.

§

And then there was Fine Line. I had heard about it from time to time but had never been there until two years ago when looking for a place to study weaving again. Weaving instruction is given along with instruction in painting, pottery, paper making, sculpturing, spinning, and knitting. Claudia Snow, writing in the Tempo section of the Chicago Tribune last December, said,

| It holds a dream that takes its form in awakening and nurturing of the creative spirit within the people who come here to visit and study. |

The Fine Line is housed in a restored barn north of St. Charles. Students are drawn from many miles to visit and then remain to study, to get in touch with their own creativity. Denise Kavanaugh, Director, with Geraldine and Peter Julian, all Sisters of St. Francis, live in the barn and operate the center. I find it interesting that each of these women had teaching careers for many, many years. Their religious order has a history of encouraging the sisters to respond to societal needs, to grow in the use of their own gifts, and to share them with others. I went to Fine Line with a great social and personal need to re-establish personal self-esteem and become a giving person again. I wanted to learn to weave and found a center with a mission statement which includes:

|

The world is hungry for artistic expressions of the spirit. Within each person lies creative energy. Release of creative energy enhances self-esteem. Awareness of creative power enables people to improve their lives and the lives of those they teach. |

Denise is the best teacher I have ever observed. Because I am a slow weaver (please note -- I did not say slow learner), I am in the loom room many hours and have observed her teaching many classes in beginning weaving as well as advanced classes using difficult, intricate patterns. I have heard her say to beginners, as she said to me, "If you can count to four you can learn to weave."

The mission statement further includes:

|

The value of the artistic experience is not only personal but has ramification which affects family and community life. The center will provide an atmosphere for releasing and channeling creative energies. The goal of our curriculum will be to provide good instruction, valuable learning experiences, and quality leisure activities for the public we serve. |

Since Fine Line opened about 11 years ago, it has moved twice to have more space -- the last time to the huge barn. Presently, planning is under way for expansion at that site. A group of at least fifty volunteers actively assist in the operation of the center. Denise just says simply, "Something always happens." I say, "A way will open."

I have shared with you how in my early experiences I discovered a process for learning/teaching which served me a lifetime in the "education" world. I found a similar process effectively utilized at Fine Line which helps me be whole again as well as having a passing ability to weave.

My wish for all of you is that somewhere you, too, may have your special "Fine Line" where you can heal, grow, perhaps forgive, perform, and look forward to your creative spiritual journeys. Let us be especially patient with ourselves as we search for ways to love creatively and spiritually. Writing this paper has been an adventure in self-discovery as well as self-understanding. It puts the past to rest. Thank you most sincerely for giving me this gift.

References

Burns, David D., MD. Feeling Good. New York: William Morrow and Company, Inc., 1980.

Cheatham, Anne and Powell, Mary Clare. This Way Day Break Comes. Philadelphia, PA: New Society Publishers, 1986.

Coffin, William; Coles, Robert; Updike, John; Wattleton, Faye. Making the Spiritual Connection, Lear's (New York, NY) Dec. 1969.

Fox, Matthew. Original Blessing. Santa Fe, NM: Bear and Company, 1989.

Frank, Frederick. The Awakened Eye. New York: Vintage Books, a Division of Random House, 1979.

Miller, Larry. Spiritual Aspects of Depression, Friends Journal (Philadelphia, PA) September 1987.

Miller, William C. The Neuropsychology of Creativity. (16 tapes) Mill Valley, CA: The Global Creativity Corporation, 1989.

Packard, Vance (alias Robert Crandall). They Won Their Fight for Better Schools. American Magazine (New York) May 1954.

Richards, Mary Caroline. Centering in Pottery, Poetry, and the Person. Middleton, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1962.

Robbins, Lois B. Waking Up in the Age of Creativity. Santa Fe, NM: Bear and Company, 1985.

Sutton, Ann and Sheehan, Diana. Ideas on Weaving. Loveland, CO: Interweave Press, 1989.

IYM Home | About IYM | Calendar | Member Meetings | Publications | Search