|

|||

|

|

|

SUMMER, 2001: Volume 6, Issue 2 Non-violence in Rwanda by Peter Yeomans�Trying to put the squares together made me think of how we are trying to put our country back together after what happened. Everyone wants peace now, but we must look to each other for help to get there. We can�t do it by ourselves.� � Participant�s comment on debriefing of �Broken Squares� exercise.

Ultimately, it is very difficult to know what impact many peacebuilding

programs have. So many factors � both positive and negative � contribute

to the presence of violence and to the presence of peace. Some of Alternatives

to Violence Project�s (AVP) credibility and value must be taken on faith.

Yet, I believe there are specific reasons to be hopeful about the impact

of AVP in Rwanda. I am much more convinced of its value and relevance

as we complete Phase I of the AVP-Rwanda project than I was before we

started.

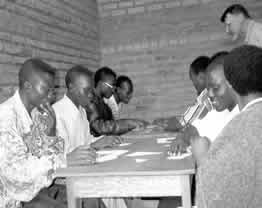

Time and time again participants commented on how different the AVP

workshop was from others. �We have been to so many workshops on peace

and on reconciliation � but this one is different! We are not bored.

Everyone is staying.� In every workshop I was involved in, the level

of participation increased over the course of the three days. If someone

came late the first day, everyone was on time for the other days, and

we always ended up with more participants than when we started. I believe

AVP has its own niche in the milieu of peacebuilding workshops in Rwanda,

and has successfully garnered people�s attention and interest, because

of its experiential philosophy and extremely grass-roots, bottom-up

approach. Most workshops and seminars present theories and strategies

in a top-down approach, while AVP facilitators reflect participants�

questions back to the group and insist that the answer to the problems

are in each of us. So, the games and the experiential learning with

exercises surprised people and engaged them in a refreshing way. Its

commitment to the personal, at the expense of the political and societal,

was novel and was also appreciated by our participants. The philosophy

that the �answer is within you� was also invigorating and clearly resulted

in a strong sense of empowerment. AVP meets a need, serves people in

ways they are not well served, and has a valuable role to play in Rwanda

and in the Great Lakes region.

AVP�s origin and strong suit is the prison setting. Rwanda currently

has 116,000 people in prison accused of crimes that have not been tried.

Prisons are overflowing as people wait for their trials. One prison

has approximately 12,000 inmates. AVP is uniquely poised to serve this

population and to promote healing in Rwandan prisons.

The timing is excellent to begin working with soldiers returning from

the war in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. In our last week in

Rwanda, we were suddenly seeing many soldiers in Kigali or on their

way home. Three different Rwandans that I worked with separately voiced

serious concerns as to how these soldiers will behave now that they

are back in-country and with little or nothing to do. Many people fear

killings like those suffered in 1997 in the northwest before the army

actually went more fully into the Congo war.

The participants� choices for role-play scenarios often represented

real live issues shared by many Rwandans. In a �Hassle Line� activity,

one group wanted to pretend to be Tutsis who had lost their children

in the war and Hutus whose children had been falsely imprisoned since

the war. I was a bit surprised by the intensity of the subject they

chose, and I asked them if they were all comfortable exploring that

conflict. The response seemed to be a resounding �yes� and they dove

in.

By far, the most common proposed role-play topic was that of two neighbors,

one who has cows. The cows are on the neighbor�s land. It seemed to

capture so much of the conflict, as expressed and experienced by the

average Rwandan. Two people. One has cows. The other doesn�t (but, in

our role play he was banishing a broken machete). There is a shortage

of land and a threat to personal space and security.

One of the most successful exercises we did was �Masks� during an Advanced

workshop. After one group got to enjoy oppressing the other according

to the rules of the exercise, Joseph Semate made the insightful decision

to then have them switch roles. I had thought the point had been made,

and it wasn�t necessary to continue, but Joseph made a great choice.

It was incredible to watch the new people in power, after having been

oppressed by the other group, get revenge. Both sides clearly enjoyed

their choices to have the power, but it was the second group in particular

that relished their opportunity to mete out revenge. In the debriefing,

people readily admitted to these feelings and we had a moving and valuable

discussion about power and oppression in Rwandan society.

Definitely, the high point for me was watching the newly trained Rwandan facilitators work on the first day of the Basic workshop they led in Kibungo. Having stayed up late the night before to be thoroughly prepared, they leaped into their new roles with enthusiasm and conviction and energy that I had not seen in them when they were participants. They convincingly handled different questions from hesitant participants and remembered an assortment of details and nuances that I hadn�t expected the first time around. Joyce and Pierre in particular each facilitated an exercise in which I could clearly see the pleasure and satisfaction in their faces as the participants� comments in the debriefing were insightful and profound. They knew they had expertly facilitated an exercise and they were reveling in listening to the learning that they had sparked. Simultaneously, participants were empowered as they articulated their own learnings and insights, and the new Rwandan facilitators were empowered as they witnessed the fruits of the tools they had learned to use.

Peter Yeoman (US) and George Walumoli

The Ugandans and the American facilitators formed a successful partnership

and were definitely necessary complements to each other. Despite carefully

shared decision-making, the situation still challenged us to resist

the almost unconscious tendencies in which we communicate more readily

with those who are culturally similar. Though I genuinely believe that

we all got along well and shared the objective of unifying as one team,

we still needed to apply vigilant attention to avoid these tendencies.

Both Ugandans and Americans brought a wealth of AVP experience, particularly

from the prisons. The Americans seemed to have more direct ties with

the institution of AVP, while the Ugandans had the critical experience

of AVP in an African context. Joseph, George, and Vincent, had already

been through the experimental stages of trying to apply an American-born

workshop to an African context, and had managed the ensuing challenges

of some necessary cultural adaptations. They therefore often had hunches

and valuable insights as to what was going to work, or how particular

exercises might be perceived. Their experience was and will continue

to be invaluable to the success of the project.

I believe that we successfully met our goals for the project and that

people worked hard to contribute as much as possible. I believe that

the design was well conceived and that David Bucura, General Secretary

of Rwanda Yearly Meeting and organizer of the AVP program in Rwanda,

did an excellent job of coordinating it all into a well organized reality.

Rwanda is now well situated to more fully establish an AVP program.

With the necessary supervision and funds, I think it can play an important

role in the healing of the people there.

TOP

• Current PTN Index • PTN

Index • HOME |

|